Introduction: Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) encompasses a spectrum of head injuries that affect the brain’s normal function, caused by an external force. The severity and manifestation of TBIs can vary significantly, necessitating a nuanced approach to classification and diagnosis. Various classification systems have been developed to categorize the degrees of severity and guide treatment strategies effectively. This review explores these systems, focusing on concussions, PCS, and TES/CTE, to illuminate the diagnostic criteria and stages defined within each classification.

1. Concussion Classification Systems: Concussion, a mild form of TBI, has multiple grading systems to assess severity.

- Nelson Grading System: Ranges from Grade 0, featuring headaches and difficulty concentrating without being stunned, to Grade 4, characterized by a loss of consciousness (LOC) for more than a minute without coma but with symptoms similar to Grade 2 during recovery.

- Ommaya Grading System: Defines concussion through a six-grade scale, from confusion without post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) to coma and death within 24 hours.

- Additional systems, such as the Jordan, Torg, and Colorado Medical Society guidelines, among others, provide varied criteria based on symptoms like confusion, PTA, LOC, and specific recovery times.

Clinical Relevance: Concussion classification systems, such as the Nelson, Ommaya, and Jordan grading systems, are designed to assess the severity of concussion based on symptoms like headache, confusion, tinnitus, amnesia, and loss of consciousness (LOC). They help in determining the appropriate level of care, monitoring progress, and making return-to-play decisions for athletes.

Advantages:

- Specificity of Symptoms: Systems like the Nelson and Ommaya grading scales offer detailed criteria based on specific symptoms and recovery times, aiding in more precise diagnosis and management.

- Guidance for Return to Activity: These systems provide a framework for making decisions about when it is safe for individuals to return to normal activities or sports, reducing the risk of further injury.

Limitations:

- Subjectivity: Many of these systems rely on subjective reporting of symptoms, which can vary significantly between individuals.

- Lack of Consensus: The existence of multiple concussion grading systems can lead to inconsistencies in diagnosis and management strategies across different practitioners and settings.

2. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Classification: The classification of TBI severity utilizes universally recognized scales such as the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and the Glasgow Outcome Scale, alongside other systems like the Mayo and Russell and Smith’s classification systems, which consider factors like the duration of PTA and the presence of focal neurologic symptoms.

Clinical Relevance: The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is a key tool in assessing the initial severity of TBI, with scores ranging from 3 to 15 based on eye, verbal, and motor responses. The GCS, along with other systems like the Mayo system and the Glasgow Outcome Scale, helps predict patient outcomes and tailor rehabilitation efforts.

Advantages:

- Widely Accepted: The GCS is universally recognized and used, facilitating communication among healthcare professionals and supporting standardized research.

- Outcome Prediction: The Glasgow Outcome Scale provides valuable information on long-term prognosis, assisting in planning for patient care and support.

Limitations:

- Initial Assessment Limitations: The GCS and other initial assessment tools may not fully capture the long-term impact of a TBI, especially in cases of mild TBI that evolve into chronic conditions.

3. Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS): PCS is classified by the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation, focusing on symptom duration, ranging from minor symptoms lasting 1-6 months to persistent symptoms extending beyond 6 months.

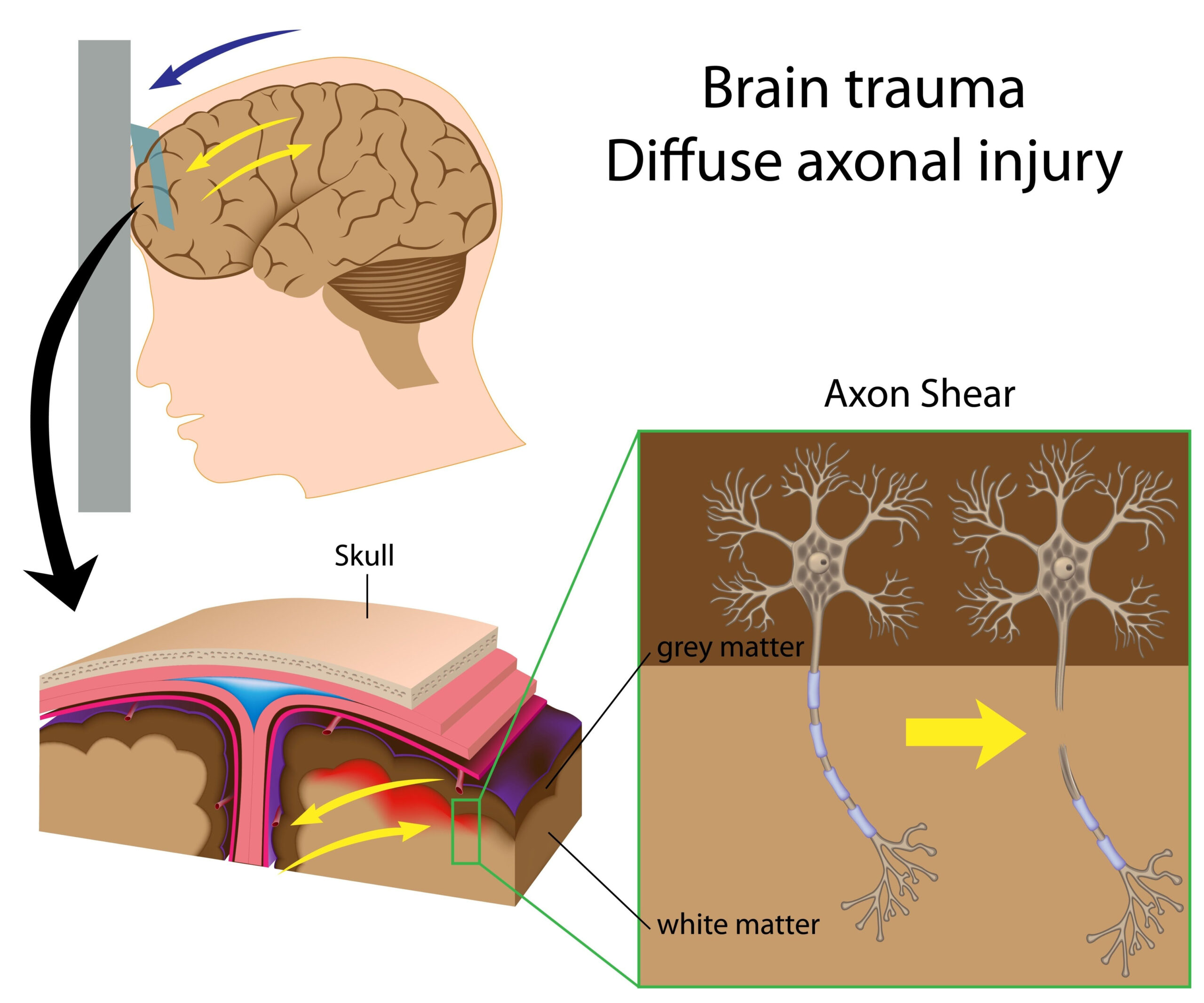

4. Traumatic Encephalopathy Syndrome (TES)/Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE): Classification systems for TES/CTE include the Jordan and Montenigro classification systems, and Omalu neuropathological classification, which differentiate cases based on behavioral/mood symptoms, cognitive impairment, and neuropathological findings.

Clinical Relevance: PCS and TES/CTE classification systems address the long-term effects of TBI. They help in diagnosing ongoing issues, such as cognitive, behavioral, and mood disturbances, which can significantly impact quality of life.

Advantages:

- Long-Term Focus: These systems recognize the prolonged impact of TBI, guiding long-term management and support.

- Inclusive of a Range of Symptoms: They acknowledge the complexity of TBI sequelae, including psychological and neurological symptoms.

Limitations:

- Diagnostic Challenges: Conditions like CTE can currently only be definitively diagnosed post-mortem, complicating the diagnosis and management of living patients.

- Overlap with Other Conditions: The symptoms of PCS and TES/CTE can overlap with other neurological and psychiatric conditions, making differential diagnosis challenging.

Conclusion: The classification systems and diagnostic criteria for TBI and related syndromes are crucial for guiding clinical decision-making and research. Understanding the nuances of these systems enables healthcare professionals to accurately diagnose and manage TBI, offering tailored interventions that address the specific needs of each patient. While the variety of classification systems for TBI and its syndromes provides valuable frameworks for assessment and management, they also reflect the complexity and diversity of brain injuries. The subjectivity of symptom reporting and the overlap with other conditions present ongoing challenges. As research progresses, these classification systems may evolve, highlighting the importance of continuous learning and adaptation in the field of neurology.

| Disorder | Classification System | Stages/Categories | Diagnostic Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concussion | Nelson Grading System | Grade 0-4 | From not stunned or dazed to LOC > 1 min |

| Ommaya Grading System | Grade 1-6 | From confusion; no PTA to coma, death within 24 h | |

| Jordan Grading System | Grade 1-4 | From confusion; no PTA, LOC to LOC > 2-3 min | |

| Torg Grading System | Grade 1-6 | From tinnitus, short-term confusion to death | |

| Colorado Medical Society guidelines | Mild, Moderate, Severe | From confusion; no PTA, LOC to LOC | |

| Cantu Grading System | Mild, Moderate, Severe | From no LOC; PTA < 30 min to LOC > 5 min or PTA > 24 h | |

| Roberts Grading System | Bell ringer to Severe | From no LOC, PTA; recovery < 10 min to LOC > 5 min; PTA > 24 h | |

| Kelly and Rosenberg Grading System | Mild to Severe | From transient confusion; no LOC to brief or prolonged LOC | |

| TBI | Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) | Mild to Severe | CGS score from 13–15 to 3–8 |

| PTA Mississippi Intervals | Moderate to Severe | PTA from 1–24 h to > 24 h | |

| Mayo System | Possible to Definite—moderate/severe | From blurred vision, confusion to LOC > 30 min, PTA > 24 h | |

| Glasgow Outcome Scale | Dead to Good recovery | From lack of function in the cerebral cortex to minor physical and mental disability | |

| Russell and Smith’s Classification System | Severe to Very severe | PTA = 1–7 days to PTA = +7 days | |

| Nakase–Richardson Classification System | Moderate to Severe | PTA = 0–14 days to PTA = 29–70 days | |

| PCS | Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation | Minor to Persistent | Symptoms duration from 1–6 months to > 6 months |

| TES/CTE | Jordan Classification System | Improbable CTE to Definite CTE | From pathophysiological process unrelated to brain trauma to CTE clinical presentation and pathological confirmation |

| Montenigro Classification System | Behavioural/mood variant to Dementia variant | From behavioural and mood features to progressive cognitive decline | |

| Omalu Neuropathological Classification | Phenotype I to IV | From +NFTs and neuritic threads, -diffuse amyloid plaques to various combinations of neuropathological findings |

This table encapsulates the diverse approaches to classifying TBI and its related syndromes, reflecting the complexity of diagnosing and managing these conditions. Each system provides a framework for assessing the severity and implications of injury, guiding clinical decision-making and patient care.

Literature – further reading:

Cantu R. Concussion Classification: Ongoing Controversy. In: Sebastianelli W.J., Slobounov S.M., editors. Foundations of Sport-Related Brain Injuries. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2006. pp. 87–110. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Teasdale G., Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91639-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Nakase-Richardson R., Sherer M., Seel R.T., Hart T., Hanks R., Arango-Lasprilla J.C., Yablon S., Sander A., Barnett S., Walker W., et al. Utility of post-traumatic amnesia in predicting 1-year productivity following traumatic brain injury: Comparison of the Russell and Mississippi PTA classification intervals. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2011;82:494–499. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.222489. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Greenwald B.D., Ambrose A.F., Armstrong G.P. Mild brain injury. Rehabil. Res. Pract. 2012;2012:469475. doi: 10.1155/2012/469475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Malec J.F., Brown A.W., Leibson C.L., Flaada J.T., Mandrekar J.N., Diehl N.N., Perkins P.K. The Mayo Classification System for Traumatic Brain Injury Severity. J. Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1417–1424. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0245. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Russell W.R., Smith A. Post-traumatic amnesia in closed head injury. Arch. Neurol. 1961;5:4–17. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1961.00450130006002. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation Guideline For Concussion/Mild Traumatic Brain Injury & Prolonged Symptoms (3rd Edition), For Adults Over 18 Years of Age. [(accessed on 19 January 2022)]. Available online: https://braininjuryguidelines.org/concussion/

Reuben A., Sampson P., Harris A.R., Williams H., Yates P. Postconcussion syndrome (PCS) in the emergency department: Predicting and pre-empting persistent symptoms following a mild traumatic brain injury. Emerg. Med. J. 2014;31:72–77. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-201667. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Jordan B.D. The clinical spectrum of sport-related traumatic brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013;9:222–230. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.33. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Omalu B., Bailes J., Hamilton R.L., Kamboh M.I., Hammers J., Case M., Fitzsimmons R. Emerging histomorphologic phenotypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in American athletes. Neurosurgery. 2011;69:173–183. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318212bc7b. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]