Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is a leading cause of neurological disability worldwide, with potential long-term consequences extending far beyond the initial injury. One of the most contentious areas of TBI research is its relationship with neurodegenerative diseases, including dementia. This connection is particularly relevant in forensic contexts, where experts are often tasked with evaluating whether a specific TBI contributed to an individual’s cognitive decline. Understanding the complexities of this association is crucial for accurate assessment and litigation purposes.

Understanding TBI and Its Classification

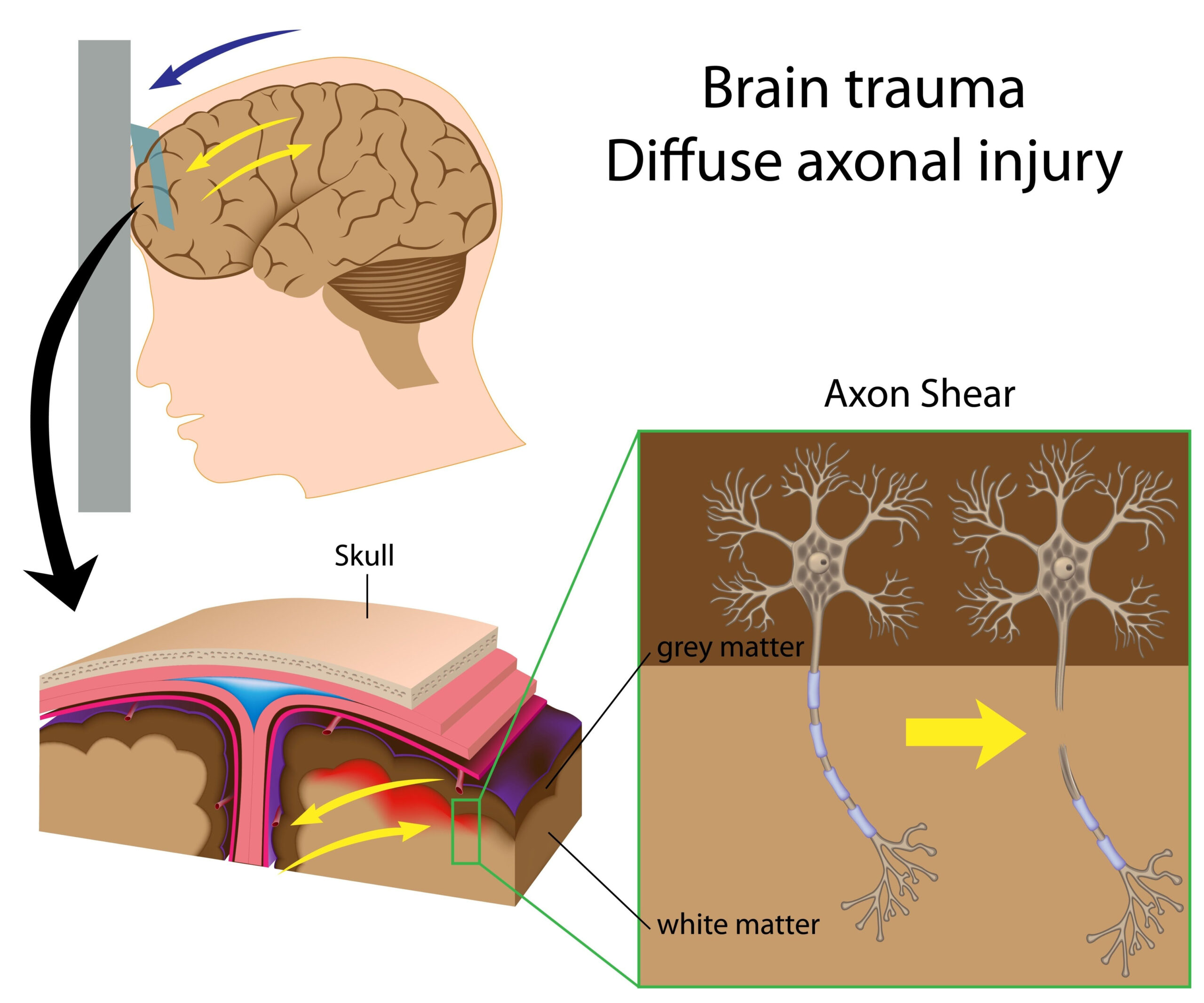

TBI encompasses a broad spectrum of injuries, ranging from mild (often referred to as concussions) to moderate and severe forms. These injuries can result from direct blows to the head, acceleration-deceleration forces, or penetrating trauma. The long-term outcomes of TBI vary widely depending on the severity, location of injury, and individual factors such as age, genetic predisposition, and pre-existing health conditions.

Mild TBI (mTBI) accounts for the majority of cases, yet its long-term effects remain a subject of debate. Most individuals recover fully within weeks to months, but a subset experiences persistent symptoms that may evolve into chronic conditions. In moderate to severe TBI, the likelihood of long-term complications, including cognitive decline and physical disability, increases significantly.

TBI and the Risk of Dementia: What Does the Evidence Say?

The question of whether TBI increases the risk of dementia has garnered significant attention in recent years. While TBI is recognized as a risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases, the relationship is complex and multifaceted. Here’s what current research reveals:

1. Prevalence and Risk:

• Moderate-to-severe TBI is associated with a slightly increased risk of developing neurodegenerative disorders, but this occurs in a relatively small percentage of cases (< 5%).

• For mTBI, the evidence linking it to dementia risk is even less clear, with studies reporting mixed results. The majority of individuals with mTBI do not develop dementia.

2. Quality of Evidence:

• The majority of studies investigating the TBI-dementia connection are observational, which limits the ability to draw causal conclusions. Many of these studies suffer from methodological issues, including inconsistent definitions of TBI, lack of control for confounding factors, and reliance on retrospective data.

3. Mechanisms of Injury:

• It is hypothesized that repetitive head trauma may lead to the accumulation of tau protein and other pathological changes associated with neurodegeneration. However, the exact mechanisms remain unclear, and the role of genetic and lifestyle factors further complicates the picture.

4. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE):

• CTE, a neurodegenerative condition linked to repetitive head injuries, has been a focal point of research. While CTE is often highlighted in media and litigation, its prevalence and clinical relevance in the general population remain poorly defined.

Challenges in Forensic Contexts

In forensic cases, evaluating the relationship between a TBI and subsequent dementia poses unique challenges:

1. Determining the Occurrence of TBI:

• Establishing whether a TBI occurred, particularly in historical cases, is often difficult. Medical records may be incomplete or absent, and self-reported symptoms can be unreliable. Forensic experts rely on comprehensive evaluations, including medical history, imaging, and neuropsychological testing, to piece together evidence of past injuries.

2. Applying Research to Individuals:

• Translating population-based research findings to individual cases is fraught with limitations. The variability in TBI outcomes and the multifactorial nature of dementia make it impossible to definitively attribute cognitive decline to a specific injury. At best, experts can discuss correlations and risk factors rather than establish causation.

3. Role of Neuropsychological Assessments:

• Forensic neuropsychologists play a critical role in assessing cognitive function and determining whether observed deficits are consistent with a TBI-related injury or other factors. These evaluations are often more comprehensive than those conducted in clinical settings, as they must withstand scrutiny in legal proceedings.

4. Confounding Factors:

• Other factors, such as age, education, vascular health, and pre-existing conditions, significantly influence dementia risk. These must be carefully considered when evaluating the impact of a TBI on cognitive outcomes.

Implications for Forensic Practice

Given the complexities of the TBI-dementia relationship, forensic experts must navigate these cases with caution and precision. Key considerations include:

1. Evidence-Based Evaluations:

• Forensic assessments should be grounded in the best available scientific evidence. Experts must acknowledge the limitations of existing research and avoid overstating conclusions about causation.

2. Differentiating TBI-Related Deficits:

• Cognitive impairments observed after TBI may overlap with other conditions, such as psychiatric disorders or age-related cognitive decline. Careful differential diagnosis is essential to avoid misattribution.

3. Education and Communication:

• In legal contexts, it is crucial for experts to communicate their findings clearly and accurately. This includes educating legal professionals and juries about the nuances of TBI and dementia research.

4. Risk Assessment Tools:

• While no tool can definitively predict dementia after TBI, emerging biomarkers and advanced imaging techniques may provide valuable insights in the future. Until then, forensic experts must rely on comprehensive assessments and clinical judgment.

Moving Forward: Research and Practice

Advancing our understanding of the TBI-dementia connection requires addressing several gaps in current research:

1. Standardizing Definitions and Methodology:

• Inconsistent definitions of TBI across studies hinder the ability to draw meaningful conclusions. Future research should adopt standardized criteria and rigorous methodologies.

2. Longitudinal Studies:

• Long-term, prospective studies are needed to better understand the trajectory of cognitive decline after TBI. These studies should account for confounding variables and explore the interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors.

3. Focus on mTBI:

• Given the prevalence of mTBI, more research is needed to clarify its potential long-term effects. This includes investigating whether certain subgroups (e.g., individuals with repeated injuries or specific genetic profiles) are at greater risk.

4. Integrating Forensic Perspectives:

• Collaboration between researchers and forensic practitioners can help bridge the gap between science and practice. Forensic input can inform study design and ensure that research findings are applicable to real-world cases.

Conclusion

The relationship between TBI and dementia is a complex and evolving area of study with significant implications for forensic practice. While moderate-to-severe TBI appears to increase dementia risk for a small subset of individuals, the evidence for mTBI is weaker and less conclusive. Forensic experts must approach these cases with a nuanced understanding of the research, acknowledging the limitations of current evidence while providing informed opinions based on comprehensive assessments.

In litigation settings, the role of the forensic neuropsychologist is critical in evaluating cognitive outcomes, interpreting evidence, and communicating findings to non-expert audiences. As research continues to advance, the integration of new knowledge into forensic practice will be essential for ensuring accurate and equitable outcomes in TBI-related cases.