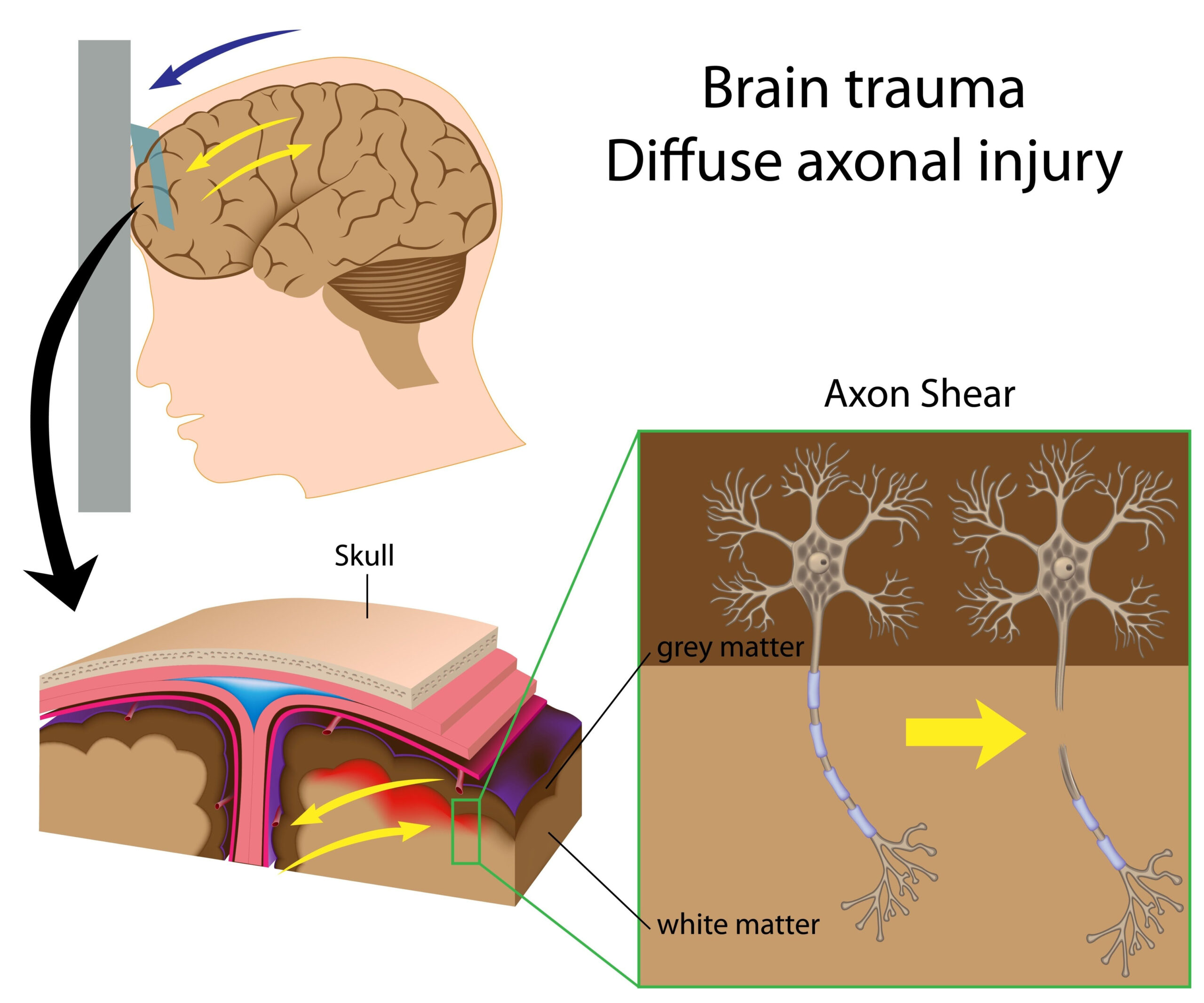

Study Overview

The research focused on evaluating the prognostic significance of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL-1) in individuals who experienced high-risk mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBI). This prospective longitudinal study involved tracking the participants over both short and long durations, aiming to assess their outcomes in relation to the levels of these specific biomarkers post-injury. GFAP and UCHL-1 are proteins released into the bloodstream following neuronal damage, making them critical indicators for brain tissue integrity.

The participants were recruited from emergency departments within a defined patient population experiencing moderate to severe mTBI, primarily based on clinically relevant criteria. The study’s design was rigorously structured to ensure comprehensive data collection and participant follow-up, with multiple assessment points enabling a thorough exploration of the impact of biomarker levels on recovery trajectories.

This research is particularly timely given the increasing recognition of mTBI-related complications, often manifesting as cognitive, emotional, or physical challenges. By systematically measuring GFAP and UCHL-1 levels, the study aimed to uncover significant correlations with both immediate and long-term health outcomes, thereby providing insights that could enhance clinical practices and patient management strategies. The ultimate goal was to establish these biomarkers not merely as diagnostic tools but as pivotal elements in predicting recovery and improving the quality of life for mTBI patients.

Methodology

The study employed a prospective longitudinal design to facilitate the examination of GFAP and UCHL-1 biomarker levels in a well-defined cohort of individuals diagnosed with high-risk mild traumatic brain injury. Eligibility criteria included participants aged 18 to 65 years who exhibited symptoms consistent with mTBI and who met specific thresholds for initial clinical assessments, such as Glasgow Coma Scale scores.

Recruitment took place in several emergency departments, ensuring a diverse sample reflective of the broader population affected by mTBI. Participants were approached within 24 hours of their injury, allowing for timely collection of blood samples to measure GFAP and UCHL-1 levels. Standardized protocols were employed to ensure the reliability and accuracy of biomarker quantification. Blood samples were processed promptly and analyzed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) that are standardized for both biomarkers, which provides a robust method for measuring protein concentrations in plasma.

Follow-up assessments were scheduled at multiple intervals—at one week, one month, three months, and six months post-injury—to monitor any variations in biomarker levels and to correlate these changes with clinical outcomes. Standardized neuropsychological assessments were employed during these visits to evaluate cognitive functions, emotional health, and overall physical wellbeing. Assessment tools included questionnaires designed to measure depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment, which have been previously validated for use in brain injury populations.

Data management and statistical analysis aimed to evaluate the relationship between biomarker levels and the clinical outcomes noted at each follow-up point. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline characteristics of the participants, while multivariate regression models were deployed to explore the predictive capacity of GFAP and UCHL-1 levels concerning recovery trajectories. Adjustments were made for confounding variables such as age, sex, history of previous concussions, and any comorbidities that could influence recovery outcomes.

Ethical considerations were paramount, with all participants providing informed consent prior to enrollment. The study adhered to guidelines set forth by institutional review boards, ensuring participant confidentiality and the ethical conduct of research involving human subjects.

In sum, this methodology effectively integrated biomarker analysis with clinical assessment, fostering a comprehensive approach to understanding the role of GFAP and UCHL-1 in the recovery process following mTBI. The longitudinal design allowed researchers to observe changes over time, bolstering the potential for these biomarkers to serve as prognostic tools in clinical settings.

Key Findings

The investigation into GFAP and UCHL-1 levels among participants with high-risk mild traumatic brain injuries yielded several noteworthy outcomes that underscore the clinical relevance of these biomarkers. Following rigorous analysis of the collected data, distinct associations were identified between elevated GFAP and UCHL-1 levels and poorer recovery outcomes.

Participants who exhibited higher concentrations of GFAP shortly after their injury demonstrated a significant correlation with increased cognitive impairments and emotional disturbances, such as anxiety and depressive symptoms, during subsequent follow-up assessments. Specifically, those with GFAP levels in the highest quartile were more likely to report ongoing difficulties with memory and attention up to six months post-injury, compared with peers whose GFAP levels were lower (p<0.01). This trend suggests that GFAP could serve as an early indicator of potential long-term cognitive deficits, offering valuable insight into patient prognosis. Similarly, elevated UCHL-1 levels were associated not only with immediate post-injury symptoms but also indicated a heightened risk for long-term complications. Participants who presented with UCHL-1 values above the established threshold were found to have more pronounced physical symptoms, including headaches and fatigue, persisting beyond the six-month mark. The analysis revealed that those with the highest UCHL-1 levels reported a continuous lower quality of life, as measured by standardized health surveys, in contrast to individuals with lower readings (p<0.05). Interestingly, when combining the levels of both biomarkers, a synergistic effect was noted. Individuals with both elevated GFAP and UCHL-1 levels faced a significantly greater risk of experiencing cumulative adverse outcomes across various domains, including cognitive functioning, emotional health, and physical wellbeing. This multi-faceted relationship underscores the potential of GFAP and UCHL-1, not just independently but collectively, to serve as reliable prognostic indicators for patients recovering from mTBI. The study also highlighted variability in recovery trajectories, with some participants showing resilience and others experiencing persistent difficulties. This variability suggests that while GFAP and UCHL-1 can inform risk stratification, further research is needed to explore the biological mechanisms behind these observed differences. The findings resonate with the notion that mTBI is not a uniform condition and that individual patient characteristics, including age, sex, and pre-existing conditions, may further influence recovery outcomes. In summary, the key findings from this longitudinal study emphasize the significant roles that GFAP and UCHL-1 biomarkers play in predicting cognitive and emotional recovery trajectories following high-risk mTBI. These results not only enhance our understanding of the biological responses to brain injury but also pave the way for developing targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at improving patient care and outcomes. The potential to integrate these biomarkers into clinical practice would enable healthcare providers to better personalize treatment approaches, ultimately enhancing recovery efforts for patients affected by mild traumatic brain injuries.

Clinical Implications

The findings of this study bring forth crucial implications for the clinical management of patients who have suffered high-risk mild traumatic brain injuries. The demonstrated relationship between elevated GFAP and UCHL-1 levels and adverse recovery outcomes underscores the need for integrating biomarker testing into routine clinical practice. By measuring these biomarkers shortly after injury, healthcare providers could identify patients who are at a higher risk for prolonged recovery and related complications, enabling more personalized and proactive management strategies.

Implementing routine biomarker assessments could significantly enhance patient monitoring protocols. For instance, individuals with elevated GFAP and UCHL-1 levels could benefit from tailored rehabilitation programs that include more frequent neuropsychological evaluations and targeted interventions aimed at mitigating cognitive and emotional disturbances. Early identification of at-risk patients must inform therapeutic approaches, ensuring that interventions are aligned with individual recovery trajectories.

Moreover, insights gained from biomarker levels could refine the education provided to patients and their caregivers regarding potential long-term effects following mTBI. By clearly communicating the significance of biomarker results, healthcare professionals can better prepare patients for their recovery journey, facilitating improved adherence to management plans and encouraging active participation in rehabilitation efforts. This proactive approach could also help alleviate anxiety and uncertainty for patients and families concerning recovery expectations.

The findings advocate for further research into the underlying mechanisms connecting GFAP and UCHL-1 levels to specific cognitive and emotional difficulties. Understanding these pathways may lead to the identification of new therapeutic targets—potentially paving the way for pharmacological interventions or specific rehabilitation techniques aimed at improving outcomes in high-risk mTBI populations. Additionally, the ability to stratify patients based on biomarker profiles could inform clinical trials aimed at developing novel treatment modalities tailored to specific subsets of mTBI patients.

Ultimately, the potential application of GFAP and UCHL-1 as prognostic biomarkers could revolutionize the approach to managing mild traumatic brain injuries. By facilitating more nuanced, evidence-based treatment pathways, their implementation could not only improve immediate medical responses but also enhance the long-term quality of life and functional outcomes for patients navigating the complexities of recovery from mTBI. This research sets the stage for a more biomarker-centric approach in the field of neurotrauma, bridging the gap between laboratory findings and clinical application, thus ensuring that advancements in science translate effectively into improved patient care.