Study Overview

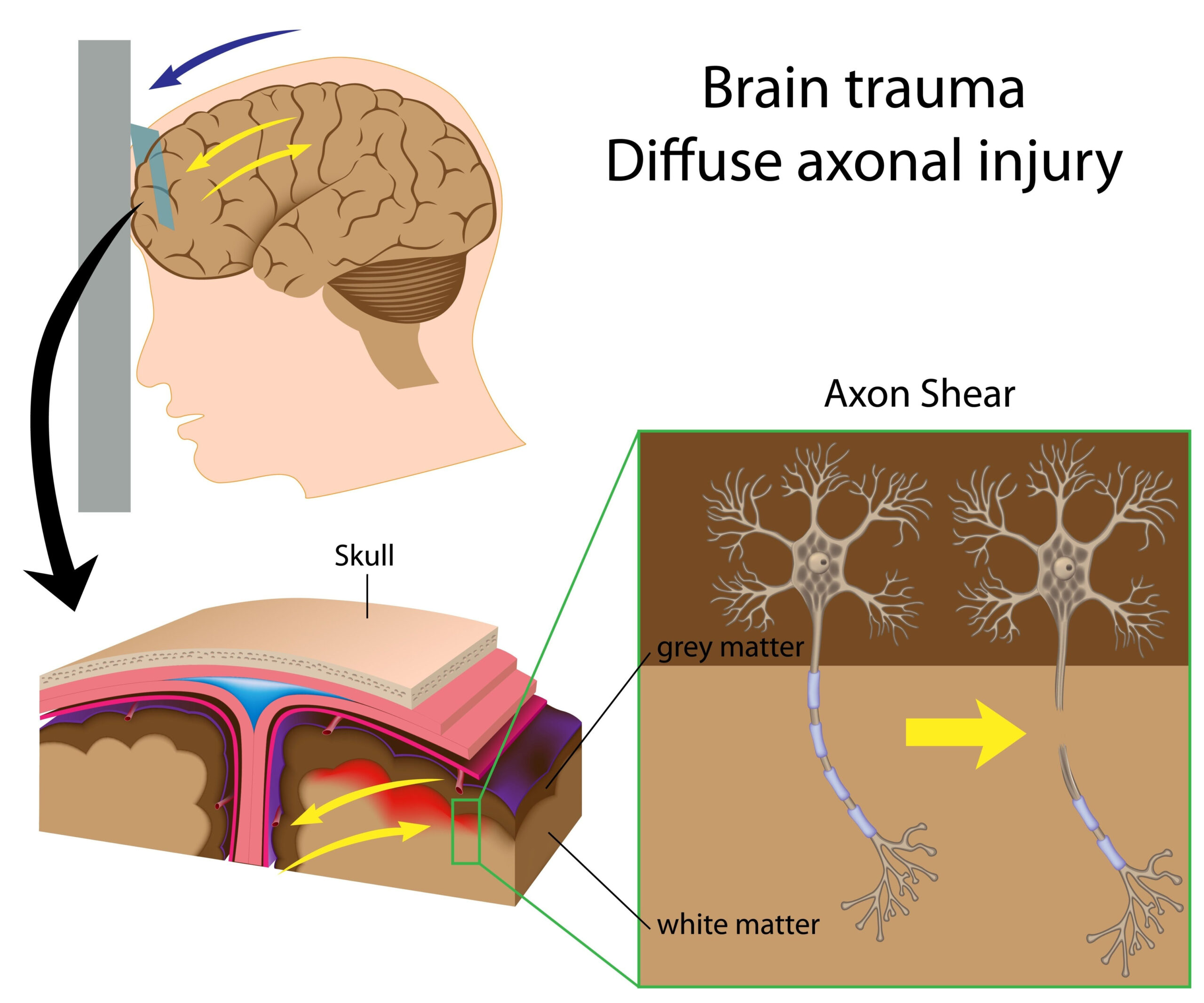

The investigation centers on the complex interplay between microglial activation and the body’s response to stress following a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). Microglia, the central nervous system’s resident immune cells, play a crucial role in maintaining brain homeostasis and responding to injury. The phenomenon of microglial priming refers to a state where microglia become hyper-responsive following an initial injury, which can predispose the brain to heightened inflammatory responses upon subsequent stressors.

In this study, researchers sought to elucidate the mechanisms through which microglial priming occurs after mTBI and its potential link to increased vulnerability to stress. They specifically focused on the HMGB1-RAGE (high mobility group box 1 – Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts) axis, a pathway known to be involved in inflammatory signaling. The hypothesis posited that following mTBI, the changes in microglial activity and the subsequent inflammatory response could have lasting effects on an individual’s psychological resilience, particularly in the face of additional stress.

By employing a combination of in vivo models and various biochemical assays, the study aimed to provide a comprehensive analysis of how earlier injuries might shape neuroinflammatory pathways and affect behavioral outcomes. The findings are positioned within the context of rising concerns about the long-term implications of brain injuries, particularly in populations such as athletes and military personnel who may experience repeated head trauma. This research is vital for understanding the foundational aspects of brain injury recovery and the factors that contribute to chronic stress responses in affected individuals, ultimately paving the way for more targeted therapeutic interventions.

Methodology

This study utilized a multifaceted approach to explore the impact of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) on microglial priming and subsequent stress responses. To accomplish this, the researchers employed both animal models and various laboratory techniques to assess the physiological and biochemical changes following mTBI.

Initially, an established model of mTBI was utilized, where rodents were subjected to controlled physical impacts mimicking mild head trauma. This approach allowed for the examination of the immediate and long-term effects of head injuries on microglial activation. Following the injury, the animals were monitored over a defined recovery period, enabling researchers to investigate the timeline of microglial response and the activation of inflammatory pathways.

Key assessments included histopathological analysis that involved the use of immunohistochemistry to visualize microglial morphology and density within specific brain regions. Markers indicating microglial activation, such as Iba1 and CD68, were measured to determine the extent of activation and any alterations in microglial phenotype. This morphological assessment was critical in deciphering the state of microglial priming characterized by hypertrophy or increased expression of inflammatory mediators.

In addition to histological evaluations, biochemical assays were conducted to quantify the levels of HMGB1 and its receptor RAGE in the brain tissue and serum. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were utilized for this purpose, providing precise measurements of cytokines and other inflammatory biomarkers linked with the HMGB1-RAGE signaling. This quantitative data helped clarify how these components fluctuate in response to mTBI and how they contribute to an exaggerated inflammatory response during stress.

Behavioral experiments were integrated into the methodology to assess the implications of microglial priming on emotional and cognitive functions. Commonly used tests such as the elevated plus maze and the forced swim test were employed to measure anxiety-like behavior and depressive-like symptoms, respectively. This behavioral analysis was essential for linking the biological findings to potential changes in psychological resilience, as it provided insights into how mTBI-related microglial changes influence overall mental health.

Data analyses were conducted using appropriate statistical methods to interpret the relationships between mTBI, microglial activation, and behavioral outcomes. Comparative analyses were made between injured and control groups to elucidate significant differences in microglial activation and resultant behavioral changes.

Overall, the methodological framework of this study combined rigorous biological assessments with behavioral evaluations to create a comprehensive picture of how microglial priming following mTBI can influence neuroinflammatory responses and susceptibility to stress, thus advancing the understanding of the underlying mechanisms involved in brain injury recovery and resilience to stress.

Key Findings

The study yielded several significant findings that enhance our understanding of the relationship between microglial priming induced by mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) and subsequent vulnerability to stress.

Firstly, the analyses revealed that microglial cells exhibited pronounced morphological changes post-injury, characterized by hypertrophy and an increased density in specific brain regions crucial for emotional regulation and cognitive functions. These changes were quantified using immunohistochemical techniques, with a notable rise in markers such as Iba1 and CD68, which serve as indicators of microglial activation. This morphological transformation suggests that microglial priming alters the baseline state of these immune cells, making them more reactive to future stressors.

Moreover, the biochemical assessments corroborated the histopathological findings, demonstrating a significant elevation in levels of HMGB1 and RAGE in both brain tissue and serum after mTBI. These results indicate that the HMGB1-RAGE axis is indeed activated following an initial injury, further implicating this pathway in mediating inflammatory responses. The marked increase in these inflammatory biomarkers provides a compelling link to the adaptive immune response, suggesting that the brain becomes primed for a heightened inflammatory reaction upon facing additional stressors.

Behavioral analysis extended these biological insights by establishing a correlation between microglial activation and adverse emotional and cognitive outcomes. Rodent subjects that underwent mTBI displayed increased anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors in standardized tests. For instance, results from the elevated plus maze indicated that the mTBI group spent significantly less time in the open arms, a common measure of anxiety, compared to controls. Similarly, the forced swim test results illustrated reduced mobility in the mTBI group, suggesting heightened depressive-like symptoms. These findings underscore the notion that altered microglial activity and the related inflammatory cascade may predispose individuals to mental health challenges, which is critical for understanding the broader implications of mTBI.

Another important discovery was the time-dependent variability in the activation state of microglia and the associated behavioral outcomes. The study identified distinct phases of microglial reactivity—immediately following injury and at later recovery points—highlighting that the neuroinflammatory landscape evolves over time. Initially, a robust activation response was observed, which later transitioned into a state of chronic inflammation that correlated with prolonged behavioral deficits. This temporal aspect emphasizes the need for ongoing monitoring and intervention strategies in individuals who have suffered mTBI.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that microglial priming following mild traumatic brain injury not only alters the immediate inflammatory response but also has long-lasting effects on psychological resilience. The implications of this research are profound, suggesting that early detection and modulation of microglial activity could potentially mitigate the risk of developing anxiety and depression following head injuries. These insights pave the way for future studies aimed at developing targeted therapies focused on the HMGB1-RAGE axis and microglial modulation to enhance recovery outcomes for individuals affected by mTBI.

Clinical Implications

The implications of the study’s findings are particularly significant for clinical practices surrounding mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) and its psychological consequences. Given the established link between microglial priming, neuroinflammation, and increased vulnerability to stress-related disorders, this research underscores the urgent need for improved screening and intervention strategies in at-risk populations, such as athletes and military personnel.

One of the primary clinical concerns is the prolonged and evolving nature of neuroinflammatory responses in patients post-mTBI. The identified time-dependent changes in microglial activation present a challenge for healthcare providers, highlighting the importance of continuous monitoring of patients over time rather than a one-time assessment immediately following the injury. This approach could facilitate the early identification of individuals who may develop chronic psychological issues, enabling timely and targeted therapeutic interventions.

Furthermore, the activation of the HMGB1-RAGE pathway, as revealed in the study, suggests a potential therapeutic target for those affected by mTBI. Modulating this signaling pathway may offer a novel strategy for mitigating the heightened inflammatory responses that predispose individuals to stress. For example, pharmacological agents that inhibit HMGB1 or block RAGE could be explored as treatments to reduce the risk of anxiety and depression in patients with a history of mTBI. Clinical trials targeting these mechanisms could provide insights into the effectiveness of such strategies in altering the course of recovery and improving mental health outcomes.

In addition to pharmacological approaches, the findings advocate for integrating behavioral health support into post-mTBI care. Given the demonstrated link between altered microglial activity and emotional dysregulation, mental health evaluations should become a standard component of care plans for individuals with mTBI. Psychotherapeutic interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), may be beneficial in addressing the cognitive and emotional challenges linked to these brain injuries. Early psychological support could mitigate the development of chronic stress responses and foster resilience among those affected.

Education and awareness also play pivotal roles in the clinical implications of this study. Educating patients, caregivers, and even medical professionals about the potential for long-term impacts following a mild traumatic brain injury is essential. Increased awareness can empower individuals to recognize early signs of psychological distress and seek appropriate help, thus enhancing their overall recovery trajectory.

Finally, the collaboration between researchers, clinicians, and policymakers is vital to translate these findings into practice. Developing clinical guidelines based on research findings can ensure that evidence-based practices are implemented effectively in treating mTBI and associated mental health conditions. This collaborative effort is essential to advance our understanding of neuroinflammation in the context of brain injuries and to establish comprehensive care pathways that address both physical and psychological needs of affected individuals.

Overall, the clinical implications of this study emphasize the necessity for a holistic approach to mTBI management that prioritizes the detection and treatment of neuroinflammatory processes while simultaneously addressing the emotional and cognitive health of patients. This multifaceted strategy could significantly improve patient outcomes and enhance the quality of life for those impacted by mild traumatic brain injuries.