The relationship between mild traumatic brain injury (mild TBI) and cognitive impairment has become a critical area in contemporary neurological research. Understanding the link requires a closer look at how even seemingly minor head traumas can initiate complex biological and psychological processes that affect brain function over time. Mild TBI, often resulting from sports injuries, minor car accidents, or falls, was historically considered to have little to no long-term impact. However, recent insights are reshaping this perception, highlighting subtle yet significant cognitive decline that can emerge weeks, months, or even years after the initial injury.

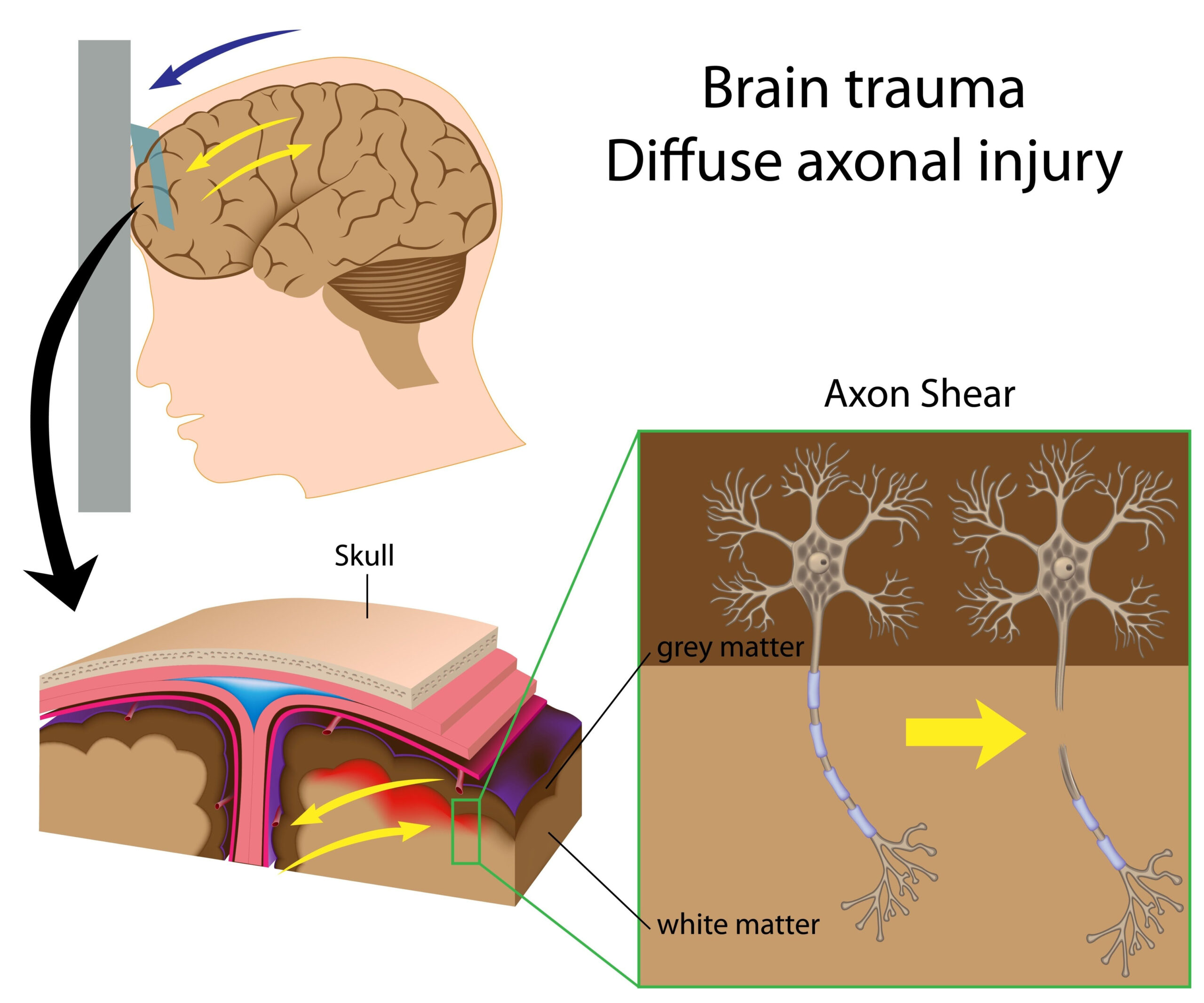

At the core of this connection is the brain’s response to trauma, which may involve diffuse axonal injury, inflammation, and metabolic disruption, even when initial symptoms appear mild or resolve quickly. These alterations can interfere with critical cognitive functions such as memory, attention, processing speed, and executive function. For some individuals, the brain’s natural plasticity and resilience enable recovery, but for others, the damage sets in motion degenerative processes that can lead to persistent impairments.

Scientific discourse around “How Mild TBI and Cognitive Impairment is Shaping Neurology” reflects the growing understanding that even low-grade brain injuries are not benign. They can set the stage for neurodegenerative diseases such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), early-onset dementia, or exacerbate other neurological conditions. Recognising how mild trauma impacts cognitive health is crucial for early intervention and for developing therapeutic strategies aimed at mitigating long-term consequences.

The complexity of this relationship also points to the importance of both subjective and objective assessments. While many individuals report cognitive difficulties following a mild TBI, formal neuropsychological testing can reveal deficits that might not be immediately apparent. This underscores the need for heightened clinical awareness and the integration of advanced diagnostic tools to detect and address these subtle yet impactful changes early on.

Factors influencing the connection

Several factors can influence the connection between mild TBI and subsequent cognitive impairment, making the relationship far from straightforward. One such factor is the severity and location of the initial injury, even when classified as “mild.” Different brain regions play distinct roles in cognitive processes, and injury to critical areas such as the frontal or temporal lobes can have a disproportionate impact on cognitive functions like memory, problem-solving, and emotional regulation.

Age at the time of injury is another significant determinant. Younger brains generally exhibit greater neuroplasticity, potentially allowing for better recovery after injury. However, in older adults, a mild TBI may exacerbate or accelerate pre-existing vulnerability to cognitive decline, a concern that is contributing to discussions around “How Mild TBI and Cognitive Impairment is Shaping Neurology.” Similarly, individuals with a history of repeated mild TBIs—such as athletes or military personnel—face a compounded risk, as cumulative damage can be considerably more deleterious than a single incident.

Genetic predisposition also plays a role. Variations in certain genes, such as the presence of the APOE ε4 allele known for its association with Alzheimer’s disease, have been shown to influence outcomes after a brain injury. Those with susceptible genetic profiles may experience more pronounced cognitive decline following a mild TBI than those without such vulnerabilities.

Socioeconomic and psychosocial elements cannot be overlooked either. Access to quality healthcare, educational background, and social support networks contribute significantly to recovery trajectories. Individuals with greater support and resources are more likely to benefit from early diagnosis, appropriate therapeutic interventions, and rehabilitation programmes, thereby mitigating long-term cognitive consequences.

Moreover, psychological factors such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) frequently co-occur with mild TBI, complicating the cognitive outcomes. The interplay between emotional health and cognitive impairment suggests the need for a holistic approach in both research and clinical practice, ensuring that both neurological and psychological needs are comprehensively addressed.

Lifestyle behaviours—including sleep patterns, diet, physical activity, and substance use—have a noteworthy impact on brain recovery and cognitive preservation after a mild TBI. Suboptimal lifestyle choices can hinder neural repair processes, exacerbating cognitive decline and highlighting the importance of patient education in managing both short- and long-term outcomes.

Evidence from recent studies

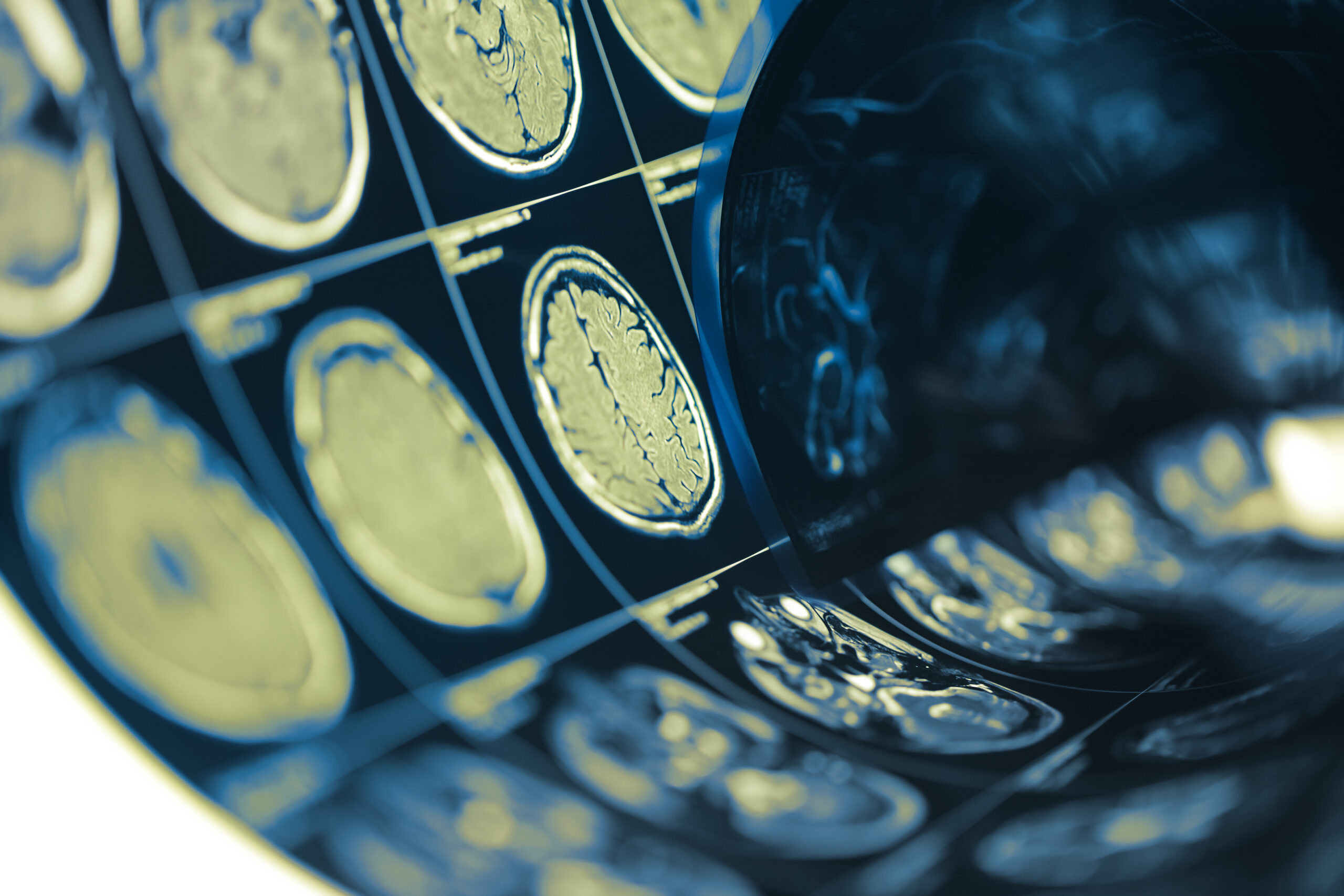

Recent studies have increasingly illuminated the intricate relationship between mild traumatic brain injury (mild TBI) and cognitive impairment, offering compelling evidence that supports the evolving discourse on “How} Mild TBI and Cognitive Impairment is Shaping Neurology.” Research published in journals such as Brain Injury and The Journal of Neurotrauma has demonstrated that even a single mild TBI can initiate changes detectable through advanced neuroimaging techniques, including diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and functional MRI (fMRI). These imaging studies often reveal microstructural damage to white matter tracts—critical highways connecting different areas of the brain—long after symptoms have ostensibly resolved.

Longitudinal cohort studies have further strengthened the link by tracking individuals over several years following a mild TBI. One notable study from a European research consortium found that individuals with a history of mild TBI exhibited greater declines in attention, executive functioning, and memory retrieval compared with matched controls, even a decade post-injury. Importantly, the risk of future neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease was found to be significantly elevated among this group, emphasising the broader implications for long-term brain health.

Additionally, research focused on athletes, particularly those involved in high-contact sports like rugby, American football, and boxing, has provided critical insights. Post-mortem examinations and in vivo studies show that repeated mild TBIs can lead to the accumulation of tau proteins, a hallmark of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). These findings lend weight to concerns that repetitive mild trauma, often dismissed historically, may embed long-lasting molecular injuries that manifest only later in life as profound cognitive and behavioural impairments.

Animal models have complemented human studies by allowing researchers to observe the biological cascade following mild TBI at a granular level. Rodent studies reveal that even mild brain injuries can lead to chronic inflammation, disrupted blood-brain barrier integrity, and the dysregulation of neural networks, providing biological plausibility for the cognitive symptoms observed clinically. Such models have been critical in testing interventions aimed at reducing post-traumatic cognitive decline.

Furthermore, meta-analyses synthesising findings from multiple studies have confirmed that mild TBI is associated with small-to-moderate but significant effects on cognitive domains, particularly attention, memory, information processing speed, and executive functioning. Although some individuals recover within months, a substantial minority demonstrates persistent impairments, contributing to growing discussions on the need for revised clinical guidelines and public health strategies.

Importantly, several studies have highlighted the moderating effects of pre-injury characteristics and post-injury management. For example, immediate cognitive rest, early multidisciplinary rehabilitation, and gradual return-to-activity protocols have been shown to improve cognitive outcomes, reinforcing the notion that how a mild TBI is managed can critically influence the trajectory of cognitive recovery or decline.

Implications for health and society

The growing body of evidence linking mild traumatic brain injury (mild TBI) to cognitive impairment carries profound implications for health systems and society at large. Recognising that even seemingly minor head injuries can lead to lasting neurological consequences compels a reevaluation of healthcare practices, particularly in fields such as sports medicine, occupational health, and emergency care. It necessitates heightened vigilance in diagnosing, monitoring, and managing patients who have suffered mild TBIs, no matter how trivial the injury might initially seem. Early intervention strategies and patient education about potential cognitive symptoms are critical steps towards minimising long-term impairment.

At a societal level, the awareness that mild TBI can contribute to chronic cognitive disorders affects our understanding of public health, workforce productivity, and caregiving needs. Each individual who experiences cognitive decline post-injury may require long-term support services, adjustments in workplace expectations, and increased healthcare utilisation, thereby exerting a considerable economic and social burden. These challenges highlight the importance of preventive measures in high-risk environments, such as enforcing stricter protocols in sports or developing safer workplace policies in industries where head injuries are common.

Education and public awareness campaigns are vital to shifting outdated perceptions that a mild TBI is an inconsequential event. Cultural attitudes, particularly in sports communities where playing through injury is valorised, must evolve to prioritise brain health and overall wellbeing. Medical professionals, educators, and policymakers must work collaboratively to disseminate information grounded in the latest research, such as findings underscored in “How} Mild TBI and Cognitive Impairment is Shaping Neurology,” ensuring that individuals at risk understand the potential seriousness of even mild injuries.

The relationship between mild TBI and mental health also demands greater integration between neurological and psychological care services. Cognitive impairments after mild TBI often coexist with conditions such as depression and anxiety, creating complex clinical pictures that require coordinated, multidisciplinary treatment approaches. Mental health support must become a standard component of care for those recovering from a mild TBI, acknowledging that emotional wellbeing is intricately linked to cognitive recovery.

From a legal and ethical standpoint, growing knowledge about the link between mild TBI and long-term cognitive issues raises questions about informed consent, responsibility, and compensation. Victims of mild TBI—whether sustained in sports, military service, traffic accidents, or the workplace—may face prolonged struggle with cognitive functions, altering their quality of life in ways that were not immediately apparent at the time of injury. Policymakers and insurers must grapple with ensuring fair access to compensation schemes, long-term support services, and protections against the inadvertent minimisation of mild TBI consequences.

The implications of this emergent understanding underscore the societal necessity to recalibrate how mild TBI is perceived, managed, and legislated. As research continues to unfold, a multidisciplinary, prevention-oriented, and patient-centred approach will be essential in addressing the wide-ranging effects that mild TBI and cognitive impairment impose on individuals and the broader community.

Future directions for research

Future research directions are pivotal for deepening our understanding of how mild traumatic brain injury (mild TBI) can lead to persistent cognitive impairments, an issue central to discussions on “How} Mild TBI and Cognitive Impairment is Shaping Neurology.” Large-scale, longitudinal studies are urgently needed to capture the long-term cognitive trajectories of individuals post-injury, allowing researchers to differentiate between temporary impairments and those that signify a progression toward neurodegenerative conditions. These studies must encompass diverse demographic groups, including different age ranges, ethnicities, and those with varying socioeconomic backgrounds, in order to provide a more comprehensive picture.

Advancements in neuroimaging technologies and biomarker identification represent promising avenues for future exploration. Researchers aim to develop more sensitive and specific diagnostic tools capable of detecting subtle brain changes in the acute phases following a mild TBI. This could enable early therapeutic intervention, potentially halting or reducing cognitive decline before it becomes irreversible. Blood-based biomarkers, in particular, are an exciting field of inquiry, as they may offer a minimally invasive method to assess and monitor injury severity and recovery over time.

Experimental treatments to promote neuroregeneration and reduce chronic inflammation following mild TBI are currently in pre-clinical and early-phase clinical trials. Stem cell therapy, neuroprotective pharmaceuticals, and targeted anti-inflammatory agents present hopeful prospects. Future research will need to rigorously evaluate the efficacy, safety, and practicality of these emerging treatments, moving steadily towards therapeutic interventions that not only address symptoms but also target the underlying pathophysiological changes induced by mild TBIs.

Another key priority for future work lies in rehabilitation science. Personalising cognitive rehabilitation programmes based on an individual’s specific cognitive profile and genetic predispositions could significantly improve recovery outcomes. Research into digital health solutions, including mobile applications and virtual reality-based therapies, offers a promising frontier for delivering personalised, accessible, and engaging interventions for those recovering from mild TBI.

Attention must also be directed towards understanding the mechanisms behind resilience—why some individuals recover fully while others develop persistent cognitive deficits. Unpacking the biological, psychological, and environmental contributors to resilience could inform better prevention strategies and therapeutic approaches. Integration of genomics, epigenetics, and lifestyle factors into this research is likely to yield nuanced insights that reshape preventative care and intervention models.

Ethical considerations must be a foundational element of future research agendas. As scientific techniques for predicting outcomes based on mild TBI improve, important questions arise about privacy, consent, and the potential for discrimination, particularly in domains like employment and insurance. Research must proceed with a commitment to upholding ethical principles while translating discoveries into clinical, educational, and public policy frameworks that truly enhance the lives of affected individuals.