Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), often referred to as concussion, is characterised by a disruption of brain function resulting from an external mechanical force. According to the latest assessment guidelines, mTBI is defined by a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13 to 15 upon initial clinical evaluation, the presence of one or more symptoms such as confusion, disorientation, loss of consciousness lasting no longer than 30 minutes, or post-traumatic amnesia lasting less than 24 hours. These criteria emphasise the typically transient and self-limiting nature of the acute symptoms associated with mTBI.

The classification of mTBI includes consideration of clinical signs, symptom patterns, and duration of neurological disruption. Assessment guidelines now highlight the importance of alongside overt symptoms, subtler cognitive impairments such as memory difficulty, attention deficits, and slowed processing speed, which may not be immediately apparent. Emotional and behavioural changes are also recognised components of the mTBI profile, including irritability, depression, and sleep disturbance, further complicating the diagnostic process.

Current frameworks also stress that imaging findings are often normal in cases of mTBI, and diagnosis is primarily clinically driven. It is critical for practitioners to apply a structured clinical evaluation that takes into account the mechanism of injury, acute functional status, physical examination findings, and the presence of any risk factors that may necessitate further investigation. Classification into uncomplicated or complicated mTBI—based on the presence of imaging abnormalities—provides additional context for prognosis and management, though even uncomplicated injuries may cause prolonged symptoms in a subset of patients.

In refining the definition, recent international consensus efforts have underscored that mTBI is a heterogeneous condition, and its classification must be sensitive to individual variability. Factors such as age, co-morbidities, injury context (for example, sports-related versus non-sporting injuries), and prior history of brain injury are now considered integral to an accurate, patient-centred classification. The updated assessment guidelines aim to support clinicians in applying a nuanced and standardised approach to the identification and documentation of mild traumatic brain injury cases.

Updated clinical evaluation protocols

Updated clinical evaluation protocols for mild traumatic brain injury focus on a more structured and comprehensive approach to early assessment. The latest assessment guidelines recommend that the clinical evaluation begins with a detailed history-taking, placing particular emphasis on mechanism of injury, initial symptoms, and any observable changes in mental status immediately following the event. Clinicians are advised to systematically inquire about periods of loss of consciousness, amnesia, confusion, and subjective complaints such as headache, dizziness, nausea, and visual disturbances.

Standardised symptom checklists and grading scales have become central to the evaluation process. Tools such as the SCAT6 (Sport Concussion Assessment Tool) and the Concussion Recognition Tool 5 (CRT5) are widely endorsed for use in sports and general settings alike, offering a consistent framework for symptom documentation and severity assessment. These instruments help ensure that subtle but significant symptoms are not overlooked during initial and subsequent evaluations.

Neurological examination remains a core component, encompassing assessments of cranial nerves, motor and sensory function, coordination, and cognitive skills. The assessment guidelines stress the importance of brief but targeted cognitive screening, which should evaluate orientation, immediate and delayed memory recall, attention span, and executive functioning. Particular attention should be paid to signs of mental status changes, including irritability, slowed responses, or emotional lability, which might indicate more severe cerebral dysfunction than initially apparent.

It is now advised that clinical evaluation is not a singular event but rather a dynamic process. Serial assessments over the first few hours after injury are considered vital, particularly to detect any evolution or worsening of symptoms that may signal complications. The guidelines encourage the use of observation protocols in a healthcare setting for a minimum of 4–6 hours where possible, especially in individuals with risk factors such as age over 65, bleeding disorders, or a dangerous mechanism of injury.

Importantly, the updated protocols advocate for clear documentation at every stage of clinical evaluation. This includes thorough records of symptom evolution, cognitive test results, physical examination findings, and patient-reported outcomes. Such documentation is critical not only for immediate management but also for informing decisions about imaging, specialist referral, and establishing a baseline for monitoring recovery over time. By following these rigorous approaches, healthcare providers can enhance the accuracy of mild traumatic brain injury diagnoses and support better patient outcomes.

Recommended imaging and diagnostic tools

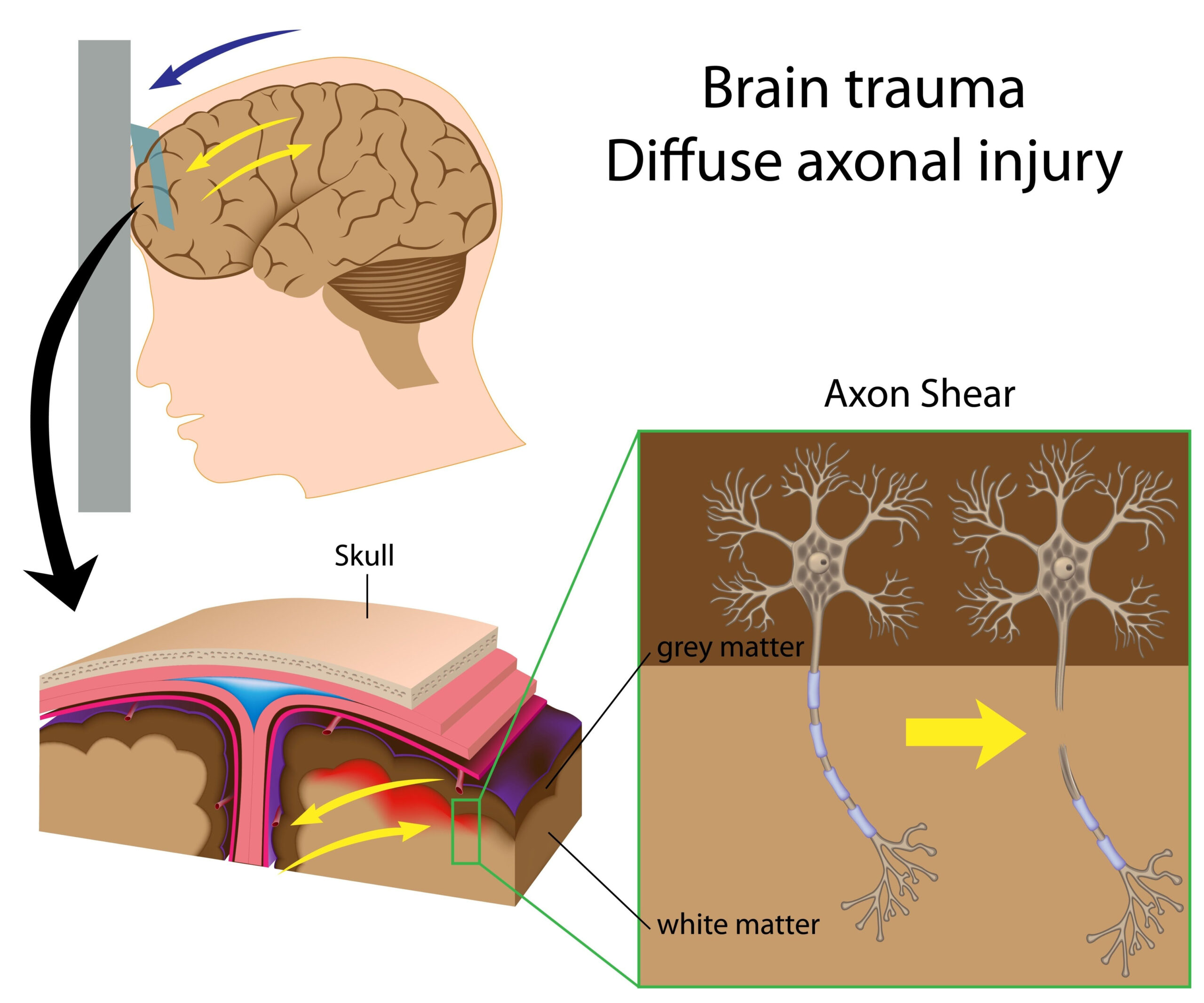

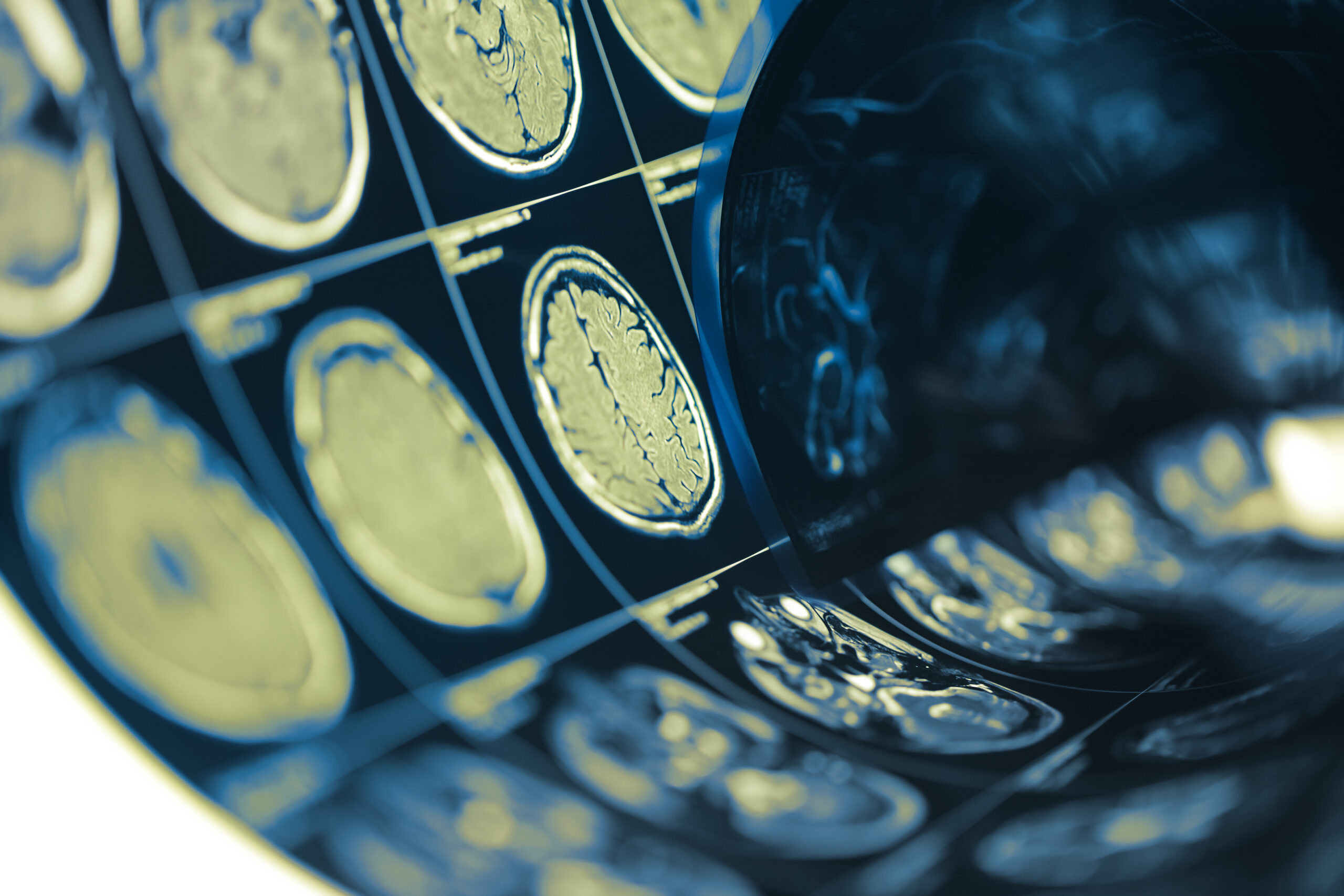

The use of imaging and diagnostic tools in the context of mild traumatic brain injury must be judicious and aligned with current assessment guidelines, as most cases do not present with structural abnormalities detectable through standard imaging modalities. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast remains the preferred initial imaging study for patients who meet specific clinical criteria, such as prolonged loss of consciousness, worsening headache, repeated vomiting, post-traumatic seizure, or signs of skull fracture. The implementation of clinical decision rules, such as the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria, is strongly recommended to guide clinicians on the appropriate use of CT scanning while minimising unnecessary radiation exposure and costs.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not routinely performed in the acute setting for patients with mild traumatic brain injury, given its lower sensitivity for acute haemorrhagic lesions compared to CT. However, MRI becomes valuable in cases where patients exhibit persistent symptoms unexplained by initial clinical evaluation and CT imaging, particularly when there is suspicion of axonal injury or microstructural brain changes. Advanced MRI techniques — including susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and functional MRI — are increasingly recognised for their ability to detect subtle injuries that may contribute to prolonged recovery or complex symptomatology.

Emerging diagnostic modalities play an evolving role in the assessment of mild traumatic brain injury. Blood-based biomarkers, such as glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), have shown promise in ruling out the need for CT scanning in certain populations. The assessment guidelines highlight that while FDA-approved biomarker platforms are beginning to support clinical decision-making, their use remains adjunctive, and should not replace thorough clinical evaluation and other standard diagnostic assessments.

Neuropsychological testing is increasingly advocated for individuals who experience persistent cognitive, behavioural, or emotional difficulties following mild traumatic brain injury. While not an imaging tool per se, these tests provide critical insights into brain function that imaging alone cannot elucidate. Comprehensive assessments of memory, attention, executive function, and mood states can help identify subtle dysfunctions and guide tailored rehabilitation strategies.

In line with best practice, the assessment guidelines strongly emphasise that diagnostic imaging and tools should be considered based on individual risk stratification and clinical context rather than applied universally. A patient-centred approach, acknowledging the heterogeneity of mild traumatic brain injury presentations, remains central to optimising diagnosis, avoiding unnecessary interventions, and supporting the recovery trajectory.

Monitoring and follow-up care guidelines

Effective monitoring and follow-up care form a cornerstone of the latest assessment guidelines for mild traumatic brain injury. A structured follow-up protocol is crucial to identify delayed complications, monitor symptom resolution, and guide decisions regarding return to work, school, or sporting activities. The assessment guidelines recommend that all individuals diagnosed with mild traumatic brain injury undergo clinical re-evaluation within 48 to 72 hours after the initial injury. This follow-up should reassess symptom burden, cognitive function, emotional state, and functional abilities to detect any emerging concerns not apparent during the first clinical evaluation.

Subsequent follow-up visits are advised to be tailored based on the patient’s clinical course. For most individuals, weekly or biweekly reviews until symptom resolution are considered sufficient. In cases with ongoing symptoms beyond 10 to 14 days, particularly where cognitive, mood, or sleep disturbances persist, specialist referral to a multidisciplinary concussion clinic or a healthcare provider with expertise in brain injury is strongly endorsed. Detailed neurocognitive testing may also be indicated at this stage to identify any lingering deficits requiring targeted rehabilitation interventions.

Monitoring strategies also underscore the importance of recognising post-concussive syndrome (PCS), characterised by prolonged symptoms such as headache, dizziness, concentration difficulties, and irritability extending beyond the expected recovery period. The assessment guidelines highlight that early identification of PCS allows for the implementation of symptom-specific therapies, psychological support, and tailored cognitive and physical rehabilitation plans, which can markedly improve long-term outcomes.

In addition to clinical monitoring, patient education is an essential component of follow-up care. Patients should be informed about the normal course of recovery, the expected time frame for symptom resolution, warning signs that warrant urgent medical attention, and strategies for symptom management. Advice on activity modification during recovery, sleep hygiene, stress reduction techniques, and gradual return to cognitive and physical tasks forms part of standard counselling during follow-up visits.

For certain populations, such as children, the elderly, and individuals with a history of previous mild traumatic brain injury, enhanced caution and extended follow-up are advised. These groups may have increased vulnerability to both delayed complications and prolonged recovery, requiring more intensive monitoring protocols. Multidisciplinary team involvement—comprising general practitioners, neurologists, psychologists, and rehabilitation specialists—is often beneficial in complex cases, ensuring an integrated and patient-centred management approach.

Throughout the monitoring process, standardised symptom rating tools are recommended to objectively track symptom progression or resolution. Instruments such as the Post-Concussion Symptom Scale (PCSS) or Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire can assist clinicians in making informed decisions about the need for ongoing care versus return-to-activity clearance. Consistent documentation of all follow-up findings remains crucial in aligning with best practice standards and ensuring a transparent, accountable care pathway under the current guidelines.

Return-to-activity considerations and patient education

Return-to-activity decisions following mild traumatic brain injury should be approached gradually, guided by the principles outlined in the latest assessment guidelines. A key emphasis is placed on the necessity for an initial period of cognitive and physical rest, where individuals restrict activities that demand significant concentration or physical exertion. However, complete inactivity beyond 48 hours is now discouraged, as prolonged rest has been associated with delayed recovery. Instead, the guidelines advocate for a staged, symptom-limited reintroduction of activities, carefully monitored through clinical evaluation to avoid symptom exacerbation.

A structured return-to-activity protocol, often referred to as a graduated return-to-play or return-to-learn plan, is strongly recommended. This involves a stepwise progression through phases, starting with light cognitive and physical activities that do not provoke symptoms. If tolerated, the individual can advance to more demanding tasks, such as schoolwork that requires prolonged focus or non-contact sports drills. Each stage should typically last at least 24 hours, and any recurrence of symptoms necessitates a return to the previous, symptom-free level for reassessment.

Specific return-to-sport guidelines, such as those developed by the Concussion in Sport Group, are frequently referenced. These recommend that athletes only resume full-contact training after medical clearance following a comprehensive clinical evaluation and are symptom-free both at rest and during exertion. For students returning to academic settings, modifications such as shorter school days, extra time for assignments, and reduced screen time may be necessary until cognitive endurance fully recovers. The guidelines stress that academic adjustments must be flexible and tailored to the individual’s symptom burden and recovery trajectory.

Patient education is integral to facilitating safe recovery and preventing secondary injury. Strong emphasis is placed on informing patients and their families about the symptoms of mild traumatic brain injury, the common trajectory of recovery, and the risks of returning to full activities prematurely. Education should include counselling about recognising signs of deterioration, such as worsening headache, repeated vomiting, unusual behaviour, or seizures, which warrant immediate medical reevaluation.

Empowering patients with realistic expectations regarding their recovery timeline is crucial. While most individuals experience symptom resolution within 7 to 10 days, the assessment guidelines acknowledge that recovery may be slower for some, taking several weeks or even months. Providing written educational materials and directing patients to reputable online resources are recommended to reinforce verbal instructions given during clinical evaluation sessions.

In workplaces, gradual return-to-work programmes may be necessary, with adjustments such as flexible hours, reduced workload, and modified duties. Healthcare providers are encouraged to liaise with employers or educational institutions where possible, ensuring that appropriate support structures are in place. For individuals with high-risk occupations, such as military personnel or industrial workers, more stringent return-to-activity criteria may be applied due to the heightened danger posed by another injury during recovery.

Ultimately, the goal is to achieve a full return to normal activities without symptom recurrence, prioritising patient safety and wellbeing. Following the staged approach advocated in the assessment guidelines allows clinicians to individualise care, reduce the risk of prolonged recovery, and optimise functional outcomes post mild traumatic brain injury.