Computed Tomography Characteristics

Computed tomography (CT) plays a crucial role in evaluating pediatric patients with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), particularly those under three years of age. The unique anatomical and physiological characteristics of this age group necessitate special attention when interpreting CT findings. In this segment, we delve into the typical CT characteristics observed in young children with mild TBI, emphasizing the need for careful analysis due to the potential differences compared to older populations.

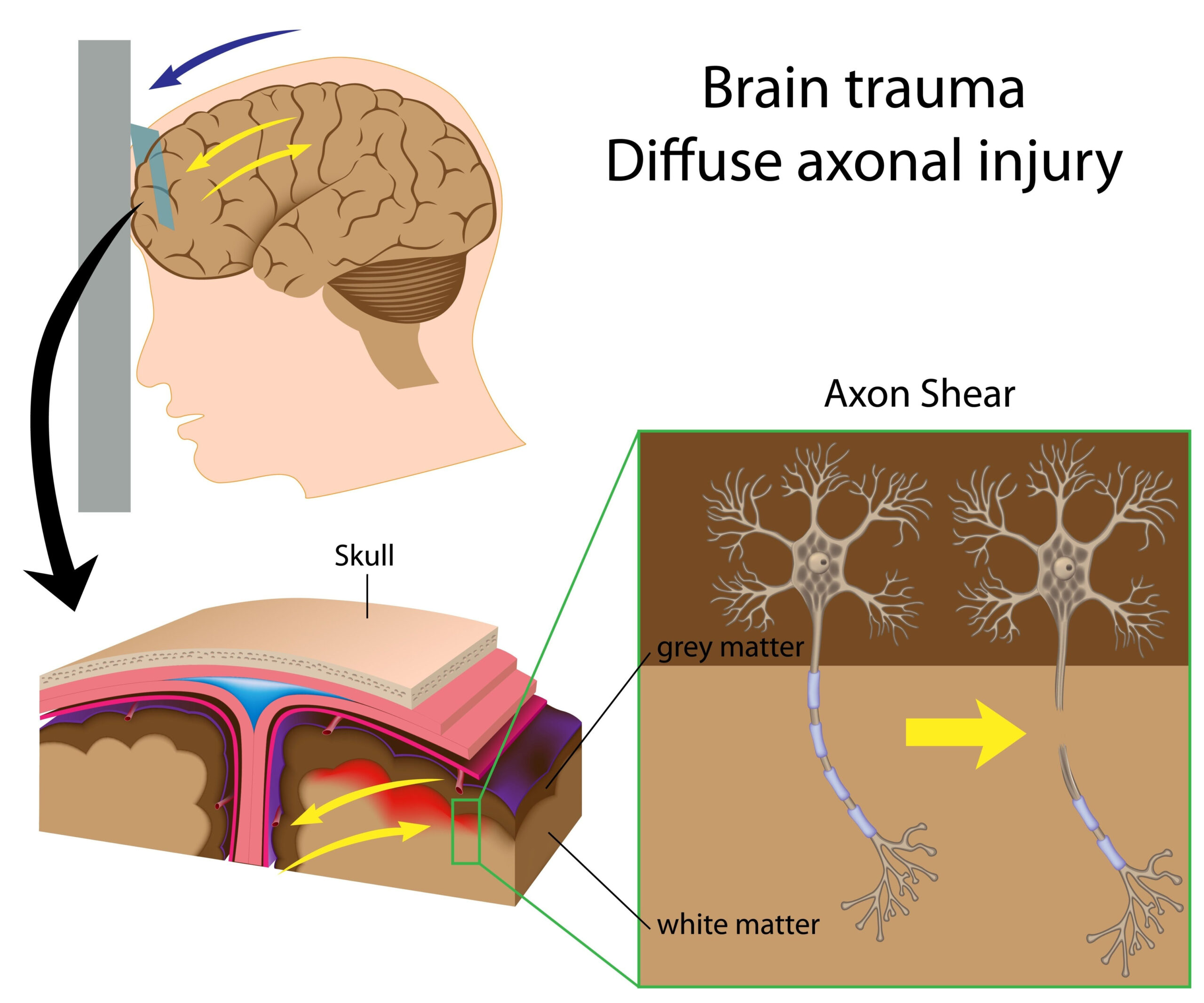

One of the most significant aspects of CT imaging in this demographic is the higher prevalence of specific injuries, such as subdural hematomas and skull fractures. Research indicates that children in this age group may present with a greater incidence of subdural hematomas due to the increased vulnerability of their developing brains and relatively larger head size in proportion to body mass. This disproportion can result in greater shear forces during trauma, subsequently leading to more severe brain injuries.

Additionally, the presence of linear skull fractures is commonly noted on CT scans of young children. These fractures may often be of minimal clinical significance, but they require thorough evaluation to rule out more complex injuries. CT imaging also has a high sensitivity in detecting parenchymal hemorrhages, contusions, and other brain injuries, which is particularly vital since initial neurological examinations may not always reliably indicate the severity of the injury.

Further complicating the interpretation of CT findings is the natural evolution of brain injuries in infants and toddlers. Changes can occur over time, and the imaging characteristics can evolve as the injury progresses. For instance, while a traumatic hematoma may not be immediately visible, follow-up scans could reveal newly developed hemorrhagic complications. Therefore, performing serial imaging can be critical to adequately assess the ongoing impacts of TBI in this young population.

Given these considerations, practitioners must approach CT findings with a nuanced understanding of their implications. The interpretation of results needs to be contextualized not only within the radiologic findings but also in conjunction with clinical symptoms and patient history. Limiting exposure to radiation while ensuring comprehensive care remains a paramount concern in pediatric imaging, necessitating an onus on healthcare providers to balance the risks and benefits associated with CT assessments in this vulnerable age group.

By recognizing the unique CT characteristics associated with mild TBI in young children, healthcare professionals can more effectively identify injuries and develop appropriate management strategies tailored to this population’s needs.

Patient Demographics and Data Collection

Understanding the patient demographics and data collection methods is vital for assessing the impact of mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) in children under three years of age. In this age group, a careful evaluation of demographic variables can illuminate patterns related to injury mechanisms, outcomes, and the effectiveness of imaging techniques. This section examines the characteristics of the pediatric population studied, along with the methodology employed to gather pertinent data.

The cohort primarily comprises children aged between zero and three years who have sustained mild TBI, characterized by a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score ranging from 13 to 15 at the time of presentation. Mild TBI is often attributed to falls, which are the most common cause in this age group due to their developmental stage characterized by exploration and increased activity. Other mechanisms, such as motor vehicle accidents and non-accidental trauma, warrant attention due to their potential to result in more severe brain injuries, despite the initial classification as mild.

Demographic data collected for each patient typically includes age, sex, weight, and ethnicity, all of which can contribute valuable context for understanding injury predisposition and outcomes. For instance, studies suggest that males are at a higher risk for head injuries compared to females, possibly due to differences in activity levels and risk-taking behaviors among young boys. Additionally, socioeconomic factors, as indicated by household income and access to childcare resources, may correlate with the frequency and nature of injuries recorded.

Data collection processes for imaging and clinical evaluation involved a systematic approach. Parents or guardians were typically interviewed to gather initial health histories, detailing the circumstances surrounding the injury. This information not only helps in establishing the mechanism of injury but also reveals any preexisting health conditions that could influence recovery outcomes, such as a history of neurological issues or developmental delays.

CT scan results were meticulously documented, highlighting any acute findings, such as hemorrhages or fractures, as well as subsequent evaluations performed during hospitalization. The time interval between the injury event and CT imaging is also critically noted, as prompt imaging can enable timely therapeutic interventions and may modify clinical decisions. Follow-up data was collected to assess the trajectory of recovery and any sequelae associated with the TBI, enhancing the understanding of long-term outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Furthermore, the analysis involved comprehensive documentation and categorization of CT findings which were then cross-referenced with clinical assessments. By correlating radiological data with clinical symptomatology, researchers can draw more meaningful conclusions regarding the implications of specific CT findings on recognition, management, and prognosis of mild TBI in young pediatric patients.

In summary, a nuanced understanding of patient demographics, combined with a robust strategy for data collection, can significantly enhance our knowledge of TBI in children under three years of age. This insight is essential for tailoring clinical approaches and improving patient care in pediatric neurotrauma.

Analysis of Imaging Results

The analysis of imaging results obtained from computed tomography (CT) scans in young children presenting with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) required a meticulous approach. The unique physiological characteristics of infants and toddlers necessitate an informed interpretation of the images, particularly considering that this population often exhibits different patterns of brain injury compared to older children and adults.

In evaluating the CT results, a systematic categorization of findings is essential. Notably, the majority of children under three years experiencing mild TBI show benign imaging results; however, a subset will demonstrate clinically significant lesions. One common finding is the prevalence of subdural hematomas, which are particularly concerning in this population due to their high incidence and potential complications. The presence of subdural hematomas can indicate a more serious underlying pathology, as they often correlate with the intensity of the traumatic event and the child’s developmental vulnerability, given the disproportion between head size and body mass.

Furthermore, it is crucial to assess the type and location of skull fractures observed in CT images. Linear skull fractures, while often benign, require careful monitoring to exclude possible associated intracranial injuries. In some cases, such fractures are accompanied by dural tears or underlying brain contusions that are not immediately apparent on initial scans but may surface during follow-up imaging, highlighting the significance of a comprehensive evaluation.

Another critical point in the analysis of imaging results is the examination of parenchymal changes. CT scans can reveal contusions, axonal injuries, and other abnormalities that may necessitate different management strategies. The detection of mini-hemorrhages within the brain’s parenchyma suggests underlying traumatic forces that may affect long-term neurological outcomes. In children, the brain is particularly susceptible to such injuries due to the ongoing developmental processes, which may not only alter the usual presentation of injury but also influence healing patterns.

In general, the timing of imaging is crucial; immediate CT scans following trauma play an important role in identifying acute brain injuries. However, because CT findings in infants and toddlers evolve, secondary imaging is often warranted. Radiologists and clinicians must be cognizant of this evolving nature of injuries and the potential for delayed symptoms, which necessitates follow-up scans for comprehensive management.

Cross-analysis of CT findings with clinical presentations serves as an indispensable tool in further understanding the implications of specific injuries. For example, the absence of acute findings on a CT scan does not exclude the potential for functional impairments, and ongoing clinical observations are critical for assessing the child’s recovery trajectory. Additionally, linking trends observed in imaging data with neurodevelopmental assessments can provide insights into long-term consequences and the nature of cognitive and motor recovery.

In conclusion, rigorous analysis of imaging results from CT scans in children under the age of three with mild TBI is essential for an accurate understanding of the injury profile. Recognizing the unique injury patterns, combined with longitudinal observational data, equips healthcare professionals with the necessary knowledge to effectively manage cases and anticipate potential challenges in recovery. This integrated approach will ultimately enhance clinical decision-making and patient outcomes in this vulnerable pediatric population.

Recommendations for Clinical Practice

In managing children under three years of age with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), the clinical approach must be multifaceted, taking into account the unique physiological characteristics of this demographic, their specific injury patterns, and the implications of imaging findings. The following recommendations serve as a comprehensive guide to practitioners who are tasked with the care and management of these young patients.

First and foremost, it is essential for healthcare providers to adopt standardized protocols for the evaluation of mild TBI in this age group. Given the potential disparity in presenting symptoms among infants and toddlers, a heightened index of suspicion for intracranial injury is warranted, especially in cases of significant mechanism of injury, such as falls from heights, motor vehicle accidents, and instances of non-accidental trauma. Utilizing established clinical guidelines, like those from the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN), can aid clinicians in determining who should receive imaging based on specific risk factors and clinical presentations.

Moreover, when considering CT scanning, practitioners must weigh the benefits against the risks associated with radiation exposure. Due to the still-developing nervous system in young children, minimizing unnecessary imaging is crucial. In many cases, clinicians may rely on clinical judgment rather than immediate imaging, reserving CT scans for situations where neurological assessment indicates a potential for significant injury. Education surrounding the appropriate use of imaging technology can also bolster decision-making processes and optimize resource utilization.

In scenarios where CT imaging is deemed necessary, it is imperative for interpreting radiologists to be thoroughly aware of the expected CT characteristics associated with TBI in toddlers and infants. Given the prevalence of subdural hematomas and possible secondary findings such as skull fractures, detailed analysis of CT scans should encompass both immediate and follow-up evaluations. Radiologists and attending physicians must communicate effectively to track any changes in imaging over time, which is essential for understanding the evolving nature of brain injury in this young population.

Furthermore, it is beneficial for clinicians to establish a follow-up protocol for monitoring children diagnosed with mild TBI who may not present with significant imaging results initially. Given that symptoms and injuries can manifest or worsen over days to weeks, follow-up visits that include clinical assessments and potentially repeat imaging should be structured into the management plan. This vigilance can be pivotal in catching delayed complications and ensuring appropriate interventions are enacted swiftly.

In addition to monitoring and imaging considerations, interdisciplinary collaboration plays a critical role in the management of pediatric TBI. Involving specialists such as pediatric neurologists, psychologists, and rehabilitation experts can provide a holistic approach to treatment, addressing not only the physical aspects of recovery but also cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Regular psychological assessments should be part of the follow-up regimen, especially for children who may be at risk for developmental delays or behavioral issues resulting from their injuries.

Lastly, education for parents and caregivers is vital. Providing information regarding the signs and symptoms of potential complications, as well as the importance of follow-up appointments, fosters greater engagement in the child’s recovery process. Resources should be made available to assist caregivers in understanding what to watch for during post-injury recovery, ensuring they feel supported and informed about their child’s health.

By integrating these recommendations into clinical practice, healthcare providers can enhance the management of mild TBI among children under three years of age. Tailoring our approach to accommodate their unique needs can ultimately improve outcomes and better safeguard these vulnerable patients throughout their recovery journey.