Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is a form of brain injury that results from an external mechanical force, typically involving a sudden impact or jolt to the head. This type of injury leads to a disruption in normal brain function, albeit temporarily in most cases. The definitions of mTBI can vary slightly depending on the medical body or institution, but it is commonly characterised by a loss of consciousness lasting less than 30 minutes, post-traumatic amnesia lasting less than 24 hours, and a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13 to 15 upon initial assessment.

Although typically described as “mild”, this classification refers only to the initial severity of the brain injury and does not necessarily predict long-term outcomes or potential complications. Individuals with mTBI may experience subtle and transient symptoms such as headache, confusion, dizziness, visual disturbances, fatigue, irritability, and difficulty concentrating. In some cases, these symptoms may persist, falling under the condition known as post-concussion syndrome.

Medical professionals often conduct neurological exams and review the patient’s history and mechanism of injury to confirm a diagnosis. However, because mTBI usually does not show up on standard imaging tests like CT or MRI, it can be challenging to diagnose definitively. This challenge is a point of ongoing consideration in the mTBI vs concussion discussion, as both terms are often used interchangeably, despite differences in context and formal use.

When engaging in a brain injury comparison, it’s important to understand that mTBI is an overarching clinical term used to capture a spectrum of neurologic impairments following minor head trauma. It sits on the mild end of the traumatic brain injury spectrum, with moderate and severe TBIs representing more profound levels of disruption and damage. Nevertheless, the immediate and long-term consequences of even a mild TBI can be significant, necessitating prompt and proper management from healthcare providers.

Understanding concussion

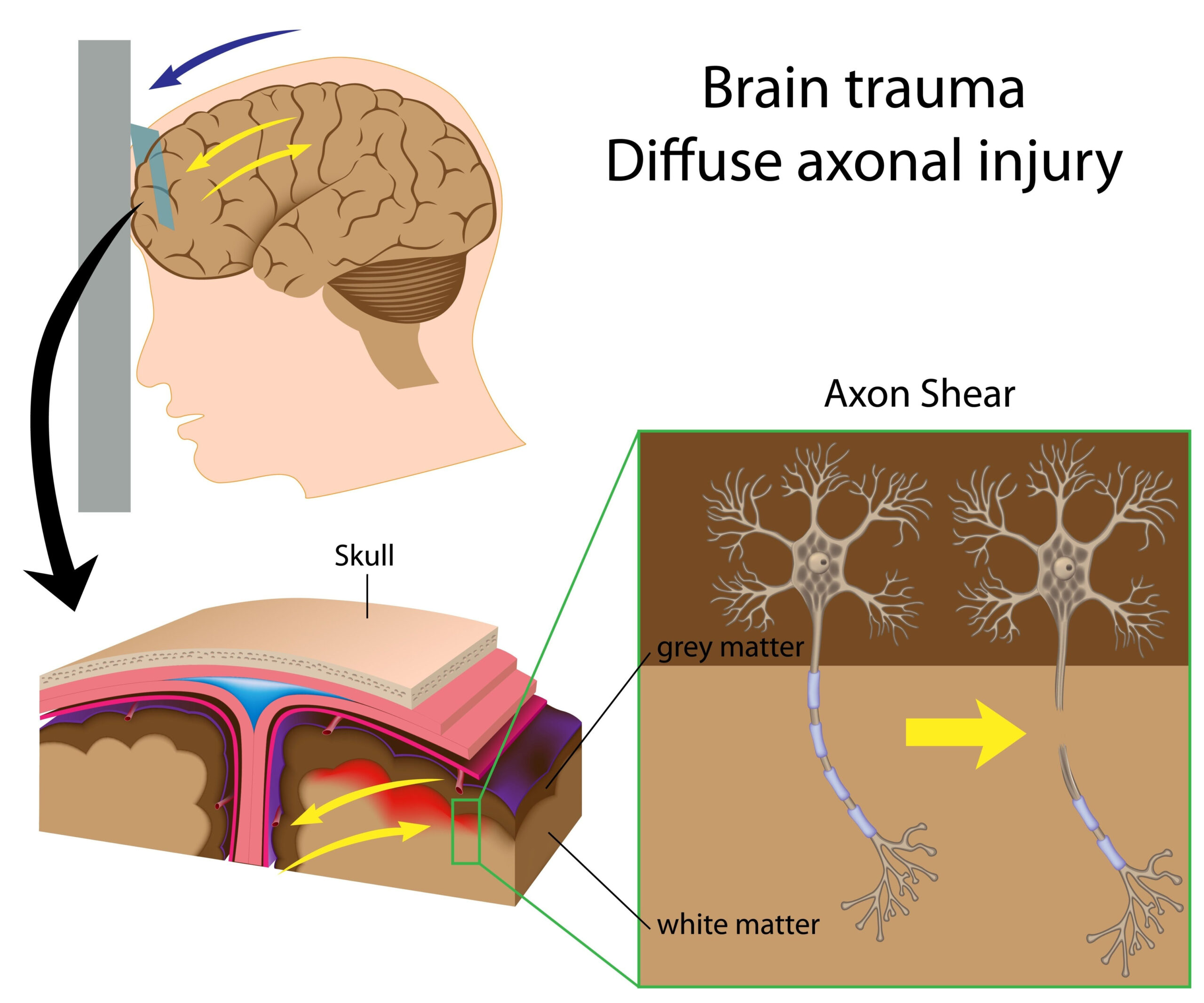

A concussion is a specific type of mild traumatic brain injury, often resulting from a blow or jolt to the head or body that causes the brain to move rapidly within the skull. This sudden movement can lead to chemical changes in the brain and sometimes stretch or damage brain cells. Clinically, a concussion is typically characterised by short-term neurological impairment and may not always involve loss of consciousness, which makes the diagnosis nuanced and reliant on symptom observation and patient history.

Common symptoms of a concussion include headache, nausea, dizziness, confusion, memory disturbance, and sensitivity to light or noise. Some individuals also report emotional changes, sleep disturbances, and difficulties with concentration or balance. These symptoms may appear immediately following the incident or develop hours or even days later. It’s not unusual for symptoms to resolve within a few days to weeks, but in some cases, they can persist, evolving into post-concussion syndrome.

In a brain injury comparison, concussions fall under the umbrella of mTBI but are frequently treated as a separate clinical entity due to their distinct profile and widespread occurrence, particularly in sports and youth injuries. The term “concussion” is often preferred in athletic and lay settings because it’s more familiar to the general public than “mTBI,” even though both share similar pathophysiological mechanisms. This popular usage has contributed to the ongoing “mTBI vs concussion” debate in medical literature and practice.

The definitions of concussion can vary slightly depending on whether one is referring to medical textbooks, sports guidelines, or legal documentation. Most agree, however, that a concussion always involves a transient alteration in brain function without structural damage visible on routine imaging. The subjective nature of many concussion symptoms and the lack of standard diagnostic tools make clinical experience and patient communication critical in identifying and managing the condition.

Understanding concussion is crucial for appropriate care and prevention, especially in settings where repeated brain trauma is a risk. Recognising the signs early and avoiding premature return to activity can significantly reduce the risk of further injury and long-term complications.

Key similarities and overlaps

In the context of brain injury comparison, mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) and concussion are closely linked, often used interchangeably in both clinical and general discussions. This overlap in terminology largely stems from the similarities in their underlying mechanisms, presentation, and outcomes. Both conditions result from biomechanical forces—usually direct impacts to the head or rapid acceleration–deceleration movements—that disrupt normal brain function on a temporary basis. Despite subtle distinctions in how they are defined or used in various settings, the overlap between them is considerable.

One of the most significant similarities lies in the symptoms experienced by individuals. Both mTBI and concussion commonly involve headache, dizziness, nausea, confusion, memory issues, sensitivity to light or sound, and alterations in mood or sleep patterns. These symptoms may appear immediately or develop gradually in the hours or days following the injury. In many cases, symptoms from either condition resolve with rest and time, though some individuals may experience prolonged difficulties known as post-concussion syndrome.

Furthermore, both conditions typically do not produce visible damage on standard imaging techniques such as CT scans or MRIs. This lack of structural findings reinforces the reliance on clinical assessment and detailed patient history to reach a diagnosis. As a result, both mTBI and concussion are considered functional brain injuries, where the disturbance is often chemical or metabolic, rather than anatomical.

Another key area of convergence is the way these terms are applied across different domains. In sports medicine and everyday language, “concussion” is often the preferred term, while “mTBI” is more common in emergency medicine and academic literature. This interchangeable use adds to the confusion and necessitates clear definitions, especially when formulating treatment plans or conducting research. In essence, while there are nuanced distinctions in formal definitions, in practice mTBI vs concussion can reflect the same clinical state, depending on the context.

Healthcare professionals often treat mTBI and concussion using identical management frameworks, with rest, gradual return to activity, and symptom monitoring forming the cornerstone of care. Moreover, both are associated with similar risks from repeated injury, particularly within a short timeframe, which can lead to more serious complications like second impact syndrome or cumulative cognitive deficits. This reinforces the importance of early recognition and appropriate follow-up for any head injury categorised under either label.

Distinct differences in diagnosis and terminology

Although mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) and concussion are often used interchangeably, there are distinct differences in how each is diagnosed and understood within various medical and professional settings. These differences are largely shaped by the context in which the terms are used, highlighting the importance of precise definitions for effective diagnosis and communication about patient care. The nuances in terminology can lead to variations in clinical practice, research methodologies and patient understanding, making the mTBI vs concussion debate a central aspect of current discussions in brain injury comparison.

From a diagnostic perspective, mTBI is a broader clinical classification encompassing a wide range of brain injuries deemed ‘mild’ based on specific neurological criteria. These include a brief loss of consciousness (if any), a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13–15, and no apparent abnormalities on neuroimaging. Concussion, however, is generally considered a subset within this spectrum, characterised more by transient neurological dysfunction than structural damage. Although the two share similar causes and symptoms, the term ‘concussion’ is often employed to describe the immediate functional effects following trauma, such as disorientation, memory gaps or visual disturbances, without the need for unconsciousness or evident physiological damage on imaging.

Terminology also diverges across different disciplines. In academic and emergency medical settings, ‘mTBI’ is more commonly used, as it aligns with formal classification systems guiding diagnosis and research. In contrast, sports medicine, education and the general public frequently favour the term ‘concussion’ due to its familiarity and perceived specificity. Athletic organisations, for instance, often develop guidelines specifically for concussion management and prevention, even though they technically address mTBI cases. This divergence emphasises the contextual nature of the terminology, where the same injury could be labelled differently depending on the observer’s background and intent.

The challenge in terminology becomes especially pertinent in legal and insurance contexts, where the definitions of a concussion versus an mTBI may influence compensation claims or treatment plans. Some clinicians prefer mTBI as a term because it encapsulates the seriousness of potential ongoing symptoms, which may not be fully acknowledged under the more colloquial ‘concussion’ label. Others argue that overuse of the term mTBI might inadvertently exaggerate a case, fuelling unnecessary anxiety or drawing diagnostic ambiguity where simpler terminology would suffice.

Ultimately, while definitions are crucial for consistent medical practice and brain injury comparison, the diagnostic distinctions between concussion and mTBI are often blurred by overlapping symptoms and shared mechanisms. This has led some specialists to advocate for a more unified approach to head trauma terminology, focusing on functional impact and recovery trajectories rather than rigid categorical labels. Until such standardisation is achieved, awareness of these terminological and diagnostic distinctions remains key to navigating the complexities of brain injury care effectively.

Implications for treatment and recovery

The implications for treatment and recovery in cases of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) or concussion are significant, particularly as both conditions often rely on clinical judgement for diagnosis rather than definitive imaging findings. Whether described using the term “concussion” or the broader label “mTBI”, the chosen terminology can subtly influence healthcare pathways, patient expectations, and long-term management strategies. Regardless of the label, healthcare professionals generally adopt a similar symptomatic treatment model prioritising rest, gradual return to activity, cognitive pacing, and ongoing monitoring for complications.

In the acute phase of management, initial focus is placed on physical and cognitive rest to allow neural recovery. This involves limiting activities that demand concentration or exertion, such as work, screen time or vigorous exercise. Many healthcare practitioners advise a supervised, step-wise reintegration into normal routines. This “return-to-learn” or “return-to-play” progression is particularly well-developed in sports medicine, where concussion protocols are a critical part of injury management frameworks. Although concussion guidelines are often specific to athletic settings, they are increasingly adapted for general clinical use in mTBI cases due to the shared biological mechanisms, reinforcing their overlap in treatment approaches in the ongoing mTBI vs concussion debate.

Recovery trajectories can differ widely from person to person, with most individuals experiencing resolution of symptoms within a few weeks. However, for some, symptoms may persist beyond the expected recovery window, leading to what is termed post-concussion syndrome. This prolonged condition can include cognitive difficulties, mood changes, and physical complaints like headaches and dizziness. Identification and early intervention in such cases are crucial, and often involve interdisciplinary care teams including neurologists, physiotherapists, psychologists, and sometimes occupational therapists.

It is particularly important that treatment decisions consider both the individual’s clinical presentation and the context in which the brain injury occurred. In a sports or workplace setting, for example, the expectations surrounding recovery may influence both the pace of return to duties and the psychological impact of the injury. Furthermore, repeat injuries—especially if sustained before full recovery from a prior episode—pose heightened risks of cumulative damage or more severe long-term outcomes. For this reason, patient education and compliance with medical advice are essential elements of effective management.

The evolving definitions and variations in terminology can also influence access to care and insurance. For instance, some healthcare systems or insurers may require a formal diagnosis of mTBI before authorising certain treatments or specialist referrals, even if the clinical picture aligns with a “concussion”. This distinction complicates brain injury comparison frameworks and underscores the need for standardised language across medical documentation, policy-making and patient communication.

Ultimately, the choice of terminology—whether to describe the injury as a concussion or mTBI—should not overshadow the individual recovery needs of the patient. Although there may be differences in language and diagnostic criteria, the core principles of brain injury treatment remain consistent: rest, gradual reintegration, symptom monitoring, and multidisciplinary support when necessary. Understanding how differing definitions can shape both clinical and personal experiences is crucial in guiding optimal recovery outcomes.