Understanding Somatic Symptom Disorder

Somatic Symptom Disorder (SSD) is characterized by the presence of physical symptoms that are distressing and disruptive but cannot be fully explained by a medical condition. The manifestations of SSD can vary widely and may include persistent pain, fatigue, gastrointestinal issues, and neurological symptoms. Importantly, these complaints are real to the individual experiencing them, regardless of the absence of a clear medical cause. The emotional and psychological aspects of the disorder are integral to understanding its impact, as individuals often experience heightened anxiety and concern regarding their health.

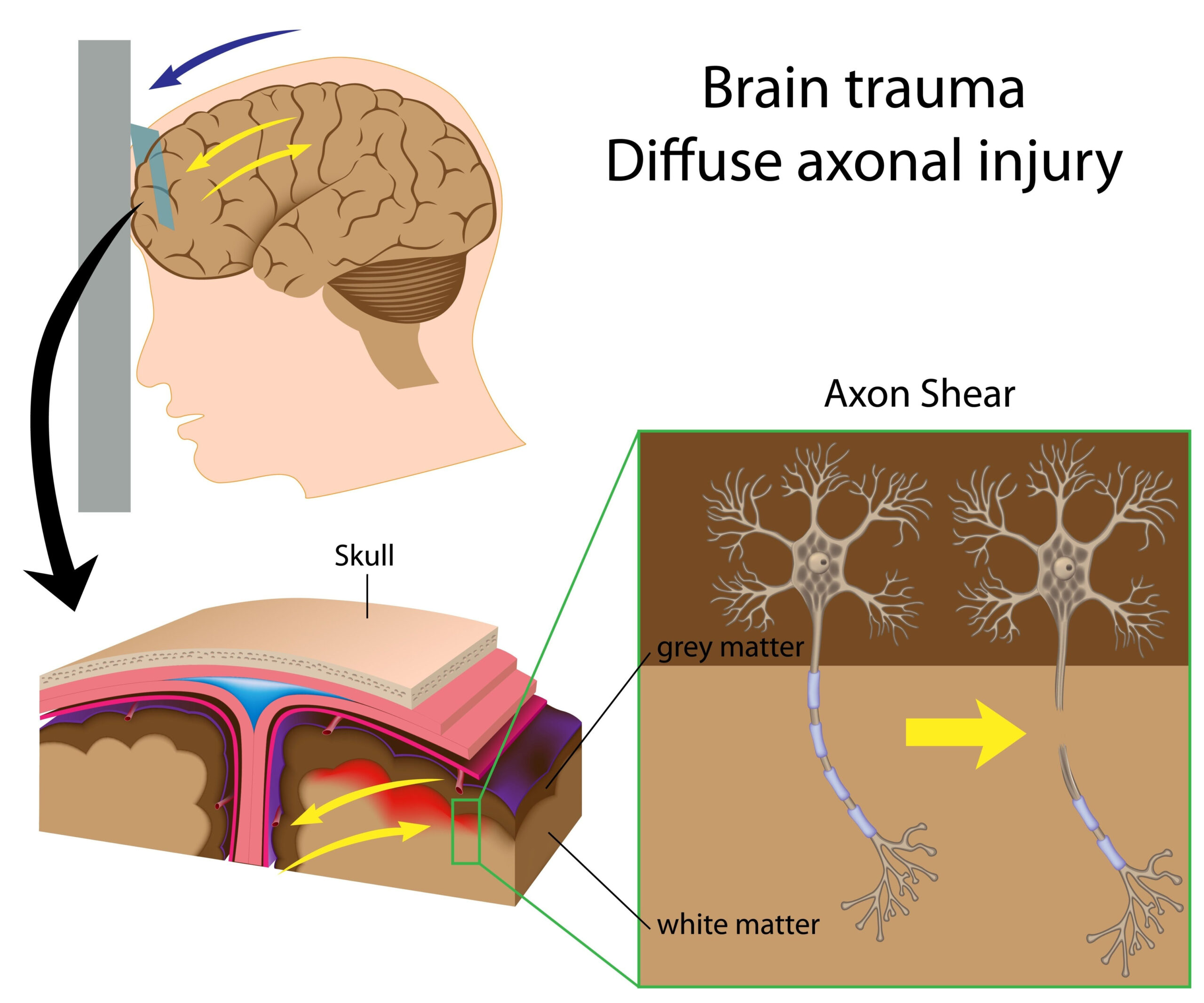

The etiology of SSD is complex and multifactorial, involving a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors. Individuals with SSD may have heightened sensitivity to physical sensations, which can lead to excessive worry and interpretations of normal bodily functions as serious medical problems. This response may be exacerbated by past experiences with illness, trauma, or stressful life events, including mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI).

Diagnostic criteria for SSD, as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), require that symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning. Additionally, the symptoms must persist for more than six months, although their specific types may fluctuate over time. Clinicians typically utilize a thorough assessment that includes a review of the patient’s history, symptoms, and any relevant medical evaluations to distinguish SSD from other medical and psychiatric conditions.

Given the subjective nature of the experience of pain and discomfort in SSD, effective communication between patients and healthcare providers is essential. This interaction not only aids in establishing trust but also enhances the understanding of the patient’s experience. Healthcare providers often play a critical role in educating patients about the nature of SSD, helping them recognize how their physical and emotional health are interconnected. Early recognition and appropriate management can improve outcomes and quality of life for individuals facing this disorder.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Individuals with Somatic Symptom Disorder (SSD) exhibit a range of symptoms that can significantly affect their quality of life. These symptoms are primarily physical in nature and can vary greatly, with common presentations including chronic pain, gastrointestinal disturbances, and neurological complaints such as headaches, dizziness, or sensory changes. Notably, these symptoms persist despite a thorough medical evaluation yielding no definitive explanation. This phenomenon underscores the core characteristic of SSD: the realness of the symptoms to the individual, regardless of any underlying medical diagnosis.

Individuals may report a primary symptom—such as severe abdominal pain or persistent headaches—but the disorder can manifest in various forms. Some patients might experience symptom exacerbation during periods of stress or psychological distress, further complicating the clinical picture. For example, someone with a history of concussive injury may find that physical sensations are more pronounced or distressing, leading to a cycle of anxiety and increased symptom reporting. This reinforces the need for clinicians to consider a patient’s mental health history when assessing symptoms.

The diagnostic process for SSD can be challenging. The clinician’s role includes not only identifying the symptoms but also discerning the absence of a medical cause that would explain them. According to the DSM-5, the diagnosis of SSD requires that the symptoms cause significant distress or functional impairment. This requires careful assessment, as symptoms can fluctuate and may overlap with other medical or psychiatric conditions, such as anxiety disorders, depression, or chronic pain syndromes.

Importantly, the duration of symptoms plays a critical role in the diagnosis; they must persist for longer than six months to meet the criteria for SSD. While this guideline can help frame the diagnosis, it is equally important for clinicians to engage in open dialogue with patients. Thorough historical and symptom reviews, supplemented by relevant medical assessments, are crucial in distinguishing SSD from conditions like orthostatic hypotension, fibromyalgia, or even serious medical diseases that might mimic somatic symptoms. This process often includes utilizing standardized questionnaires and scales that assess both the severity of the symptoms and their impact on the patient’s daily life.

Validation of the patient’s experience is a key element of the diagnostic process. Patients may often feel dismissed or misunderstood when their physical complaints are found lacking in objective medical evidence. Thus, it is essential for healthcare providers to approach this condition with empathy and a comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between psychological and physiological factors. This approach not only aids in accurate diagnosis but can also foster cooperation and trust, encouraging patients to engage in treatment strategies designed to enhance their coping skills and overall resilience.

Treatment Approaches

Treating Somatic Symptom Disorder (SSD) requires a multifaceted strategy that addresses both the physical and psychological components of the condition. Traditional medical models focusing solely on physical symptomatology often fall short of providing relief, as the symptoms of SSD are deeply intertwined with emotional and cognitive factors. Therefore, effective treatment approaches typically encompass a combination of psychotherapy, medication, and holistic care strategies, tailored to the individual needs of the patient.

Psychotherapy is a cornerstone of treatment for SSD. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has been particularly effective in addressing distorted cognitive patterns associated with illness anxiety and excessive focus on bodily sensations. Through CBT, individuals learn to challenge irrational beliefs about their health, reframe their thought processes, and develop healthier coping mechanisms. Evidence suggests that CBT can significantly reduce symptom distress and improve overall functioning. Additionally, other forms of therapy, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), have gained traction in helping patients cope with the emotional burdens associated with their symptoms. These therapies focus on enhancing self-awareness and promoting acceptance of both physical sensations and psychological distress.

Medication can also play a role in managing SSD, particularly when symptoms overlap with other mental health conditions such as anxiety or depression. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other antidepressants may be prescribed to help regulate mood and reduce the physiological aspects of anxiety. However, it is crucial that medication is used in conjunction with psychotherapy to address the underlying psychological dynamics. Medication alone may not provide the comprehensive support needed for individuals with SSD, as it does not target maladaptive thought patterns or emotional distress associated with the disorder.

Integrative and holistic approaches can further enhance treatment outcomes. Techniques such as biofeedback, acupuncture, and yoga may provide symptomatic relief and promote overall well-being by fostering a mind-body connection. These methods encourage individuals to become attuned to their physical sensations and emotional responses, potentially reducing symptom severity and improving quality of life. Introducing lifestyle modifications, including regular physical activity, a balanced diet, and adequate sleep, can create a supportive foundation for recovery. Exercise, in particular, has been shown to boost mood and decrease feelings of anxiety and depression, contributing to an overall sense of health and stability.

Collaboration among healthcare providers is central to effective treatment. A multidisciplinary approach, involving primary care physicians, mental health professionals, and allied health practitioners, can provide a comprehensive care model that addresses the multifactorial nature of SSD. This team can work together to ensure that the patient receives coherent and consistent messaging regarding their treatment, thereby reducing confusion and enhancing compliance. Regular follow-up appointments can help monitor symptoms and treatment effectiveness, allowing for timely adjustments in the therapeutic approach.

Finally, patient education is a vital component in managing SSD. Helping patients understand the nature of their disorder—particularly the interaction between physical symptoms and psychological states—can empower them to engage more actively in their treatment. This educational component can demystify their experiences and alleviate feelings of fear or stigma related to their symptoms. Encouraging self-management strategies, such as keeping a symptom diary and utilizing relaxation techniques, can cultivate resilience and foster a sense of agency over their health.

The treatment of SSD requires an empathetic, comprehensive, and individualized approach that recognizes the complex interplay between mind and body, promoting both physical and psychological healing. By integrating various therapeutic modalities and fostering a supportive patient-provider relationship, individuals with SSD can navigate their symptoms more effectively and improve their overall well-being.

Future Research Directions

Future research on Somatic Symptom Disorder (SSD) is critical, as it explores the complex interplay of psychological, biological, and environmental factors contributing to this condition. One promising area of investigation is the relationship between mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) and the onset or exacerbation of SSD symptoms. Since mTBI can lead to cognitive and psychological sequelae, understanding how these factors influence the development of SSD is vital. This could involve longitudinal studies that track individuals with mTBI over time to identify how changes in their mental health correlate with the emergence or persistence of somatic symptoms.

Additionally, the role of biomarkers in diagnosing and managing SSD is an exciting frontier. Future research could focus on identifying biological markers that correlate with the psychological distress experienced by individuals with SSD. This may include exploring neuroimaging techniques, blood tests, or other physiological measures that could offer objective data to support the diagnosis of SSD. Such advancements could enhance the clinical understanding of the disorder and reduce the stigma associated with it by providing tangible evidence of its existence.

Furthermore, there is a growing need to explore the efficacy of various treatment modalities for SSD. Although psychotherapy and pharmacological interventions have been shown to provide relief, more controlled studies are necessary to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of these approaches. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing different therapeutic options will help establish best practices for SSD treatment. For instance, a focused inquiry into the comparative effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based interventions, and pharmacotherapy could yield valuable insights into optimizing care for patients with SSD.

Another important research avenue involves investigating the impact of socio-cultural factors on the experience and reporting of somatic symptoms. Understanding how cultural beliefs, social support networks, and socioeconomic status influence symptom expression and help-seeking behavior is essential. This research could lead to more culturally sensitive approaches to treatment, ultimately improving patient engagement and outcomes. Additionally, examining gender differences in symptomatology and treatment response can further refine our understanding of SSD and tailor interventions accordingly.

Finally, the integration of technology in the management of SSD presents an exciting potential for future research. Telehealth services and mobile health applications can improve access to care, especially for individuals living in remote areas or those who face barriers to in-person visits. Studies could assess the effectiveness of these innovative delivery methods in providing psychological support and monitoring symptoms. The feasibility of using wearable technology to measure physiological responses related to somatic symptoms might enhance self-management strategies effectively.

The research directions outlined highlight the necessity of a multifaceted approach to studying SSD. As we deepen our understanding of the disorder, its interactions with mTBI, and the various treatment options available, we can pave the way for enhanced diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic efficacy. This ongoing investigation will be instrumental in mitigating the burden of SSD on patients and improving their quality of life.