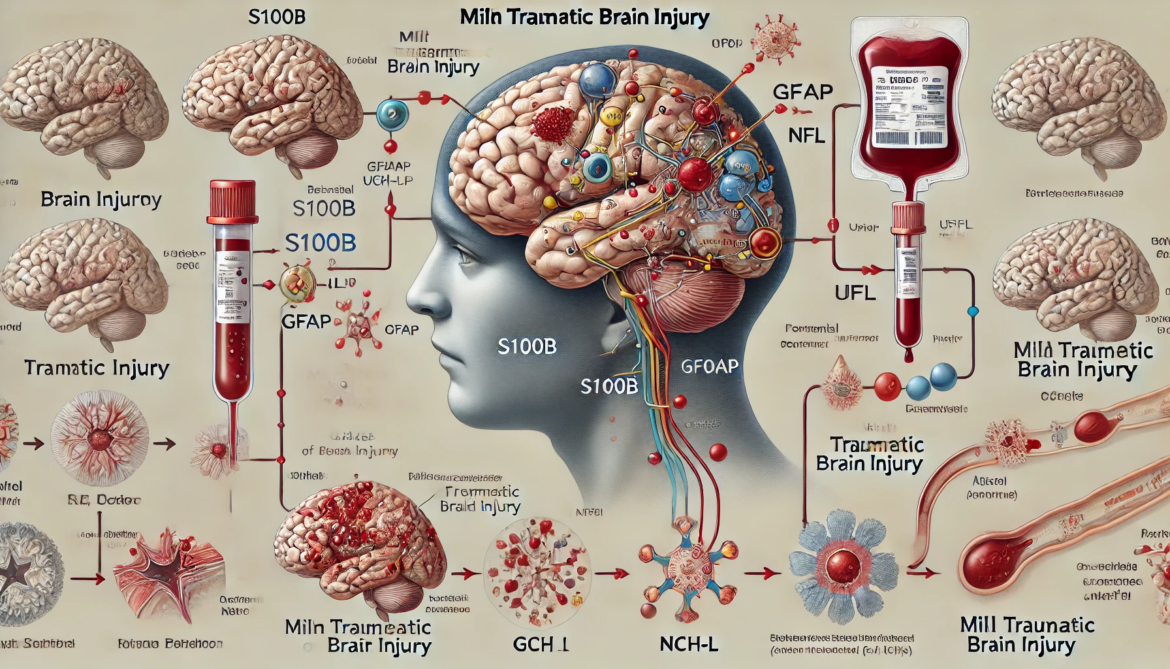

The relationship between blood biomarkers and clinical recovery in concussion, particularly mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), is a complex and evolving field. Blood biomarkers have shown promise in aiding diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring recovery, but several challenges and limitations remain.

Key Blood Biomarkers

- S100B: This protein is widely studied and included in Scandinavian and French guidelines to reduce unnecessary CT scans in mTBI patients. It is effective when measured within a few hours post-injury but has limitations due to its rapid half-life and lack of neurospecificity[4].

- Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP): GFAP is useful in detecting intracranial injuries and has been approved by the FDA for this purpose. It is particularly valuable when combined with UCH-L1, as it can be measured up to 12 hours post-injury, providing a broader diagnostic window[4][5].

- Ubiquitin Carboxy-terminal Hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1): This biomarker, also FDA-approved, complements GFAP in diagnosing mTBI. It helps in identifying patients who may need further imaging and monitoring[4][5].

- Neurofilament Light Chain (Nf-L): Nf-L levels increase following a concussion and are associated with axonal damage. However, their correlation with clinical recovery and symptom severity is not well-established[1][3].

- Tau: Tau protein levels tend to decrease after a concussion. Like Nf-L, its relationship with clinical recovery is not definitive, but it provides insights into the extent of neuronal damage[1][3].

Clinical Utility and Limitations

- Diagnosis and Prognosis: Blood biomarkers like GFAP and UCH-L1 improve diagnostic accuracy and help stratify patients based on the severity of their injury. They are particularly useful in distinguishing between patients who need CT scans and those who do not, thereby reducing unnecessary imaging[4][5].

- Monitoring Recovery: Biomarkers can track the biological processes underlying recovery. For instance, changes in biomarker levels over time can indicate the progression of recovery. However, the direct correlation between biomarker levels and clinical recovery milestones, such as symptom resolution, is still under investigation[1][3].

Unresolved Issues

Despite their potential, several unresolved issues limit the widespread clinical adoption of blood biomarkers in concussion management:

- Pathways and Kinetics: The exact pathways through which biomarkers enter the blood and their kinetics are not fully understood. This lack of knowledge complicates the interpretation of biomarker levels[1][3].

- Optimal Sampling Times: The best times to sample blood for these biomarkers post-injury are not well-established, which can affect their reliability and utility in clinical practice[1][3].

- Correlation with Clinical Measures: There is limited evidence that blood biomarker levels correlate strongly with clinical measures of mTBI severity or recovery. This weak correlation suggests that while biomarkers can provide valuable information, they should be used alongside other clinical assessments[1][3].

Future Directions

- Standardization and Validation: More research is needed to standardize the use of biomarkers and validate their effectiveness across different populations and settings.

- Pediatric Considerations: Specific studies focusing on pediatric populations are necessary, as biomarkers validated in adults may not be appropriate for children[4].

- New Biomarkers: Ongoing research aims to identify new biomarkers and refine existing ones to improve their diagnostic and prognostic capabilities[4].

In summary, while blood biomarkers offer significant promise for enhancing the management of concussions, particularly in diagnosing and monitoring recovery, further research is needed to address the unresolved issues and validate their clinical utility comprehensively.

Citations:

[1] https://biomarkerres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40364-021-00325-5

[2] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772529423010238

[3] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34530937/

[4] https://academic.oup.com/clinchem/advance-article/doi/10.1093/clinchem/hvae049/7657608?searchresult=1

[5] https://www.neurology.org/doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000207881