Study Overview

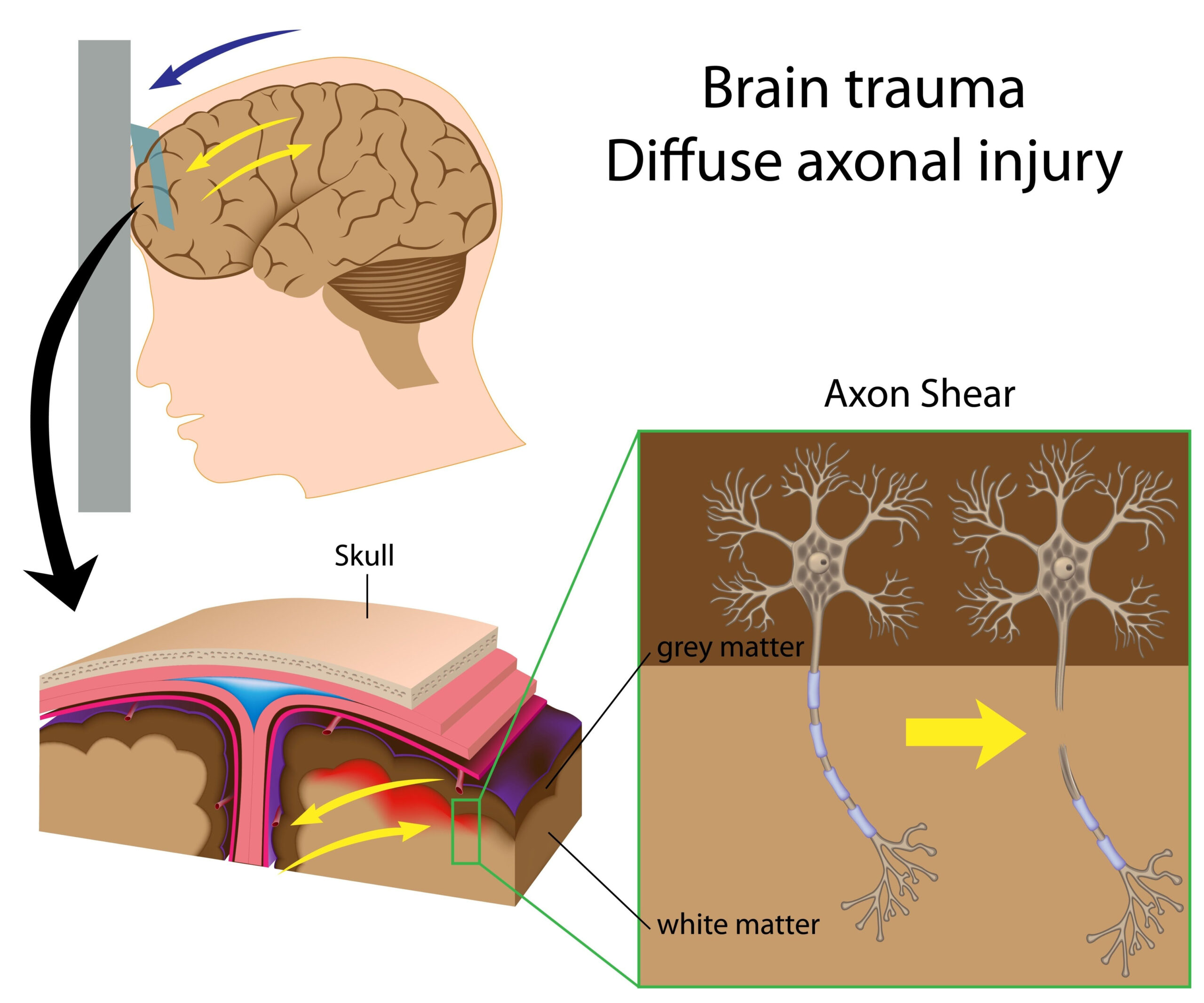

This study investigates the occurrence of low scores within the Uniform Data Set (UDS) version 3.0, specifically evaluating the differences between older adults who have a self-reported history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) and those who do not. Using a cross-sectional design, the research focuses on a population that is significant in the context of aging and neurological health. Traumatic brain injuries among older adults are of increasing concern due to their potential long-term consequences, including cognitive decline and the exacerbation of pre-existing conditions.

The UDS is a comprehensive data collection tool designed to evaluate the cognitive and functional abilities of individuals, particularly within research settings related to Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. By analyzing the scores derived from this dataset, the researchers aim to identify trends and differences that could contribute to better understanding the impacts of TBI in older populations. This inquiry is crucial as it addresses a gap in existing literature regarding how self-reported histories of TBI influence the cognitive status and overall health of older adults.

Moreover, the study seeks to clarify whether having a history of TBI correlates with lower performance on the UDS compared to older adults without such a history. This examination not only provides insights into the direct effects of TBI on cognitive health but also raises questions about the broader implications for healthcare practices and support services for the aging population. As the incidence of brain injuries in aging individuals continues to be a pertinent issue, this research stands to enhance understanding and pave the way for future interventions and studies.

Methodology

The investigation employed a cross-sectional design to provide a snapshot of the cognitive and functional status of older adults, drawing from data collected via the Uniform Data Set (UDS) version 3.0. The participant sample was specifically selected to include older individuals aged 65 and above, a demographic known to be at heightened risk for both cognitive decline and traumatic brain injuries. To ensure a comprehensive representation, researchers targeted participants from various healthcare settings that specialize in neurological assessments.

To gather data, participants were administered standardized assessments included within the UDS, which encompasses a range of cognitive measures, functional assessments, and demographic information. The assessments aimed to capture domains of cognition such as memory, executive function, and language skills, which are particularly relevant when examining the cognitive consequences of TBI. Additionally, participants underwent functional evaluations to understand their capacity for daily living tasks, integrating perspectives on both cognitive and functional health.

A pivotal part of this methodology involved determining participants’ histories of TBI. This was accomplished through self-report questionnaires where participants indicated any previous instances of brain injury, along with the severity and timing of each incident. This self-reported data was then categorized into two groups: those with a documented history of TBI and those without. The researchers ensured to include controls for various confounding factors, such as age, education level, comorbid health conditions, and social determinants of health. These controls are critical, as they allow the study to isolate the impacts of TBI history from other variables that may influence cognitive performance.

Statistical analyses were employed to compare UDS scores between the two groups. Descriptive statistics summarized the demographic profiles and cognitive performance of participants, while inferential statistics assessed the significance of differences observed in UDS scores. This included the use of t-tests and regression models to further elucidate the relationship between self-reported TBI history and cognitive outcomes. Rigorous statistical methods were necessary to ensure that the findings would be robust and meaningful, potentially offering insights that extend beyond the immediate study population.

Furthermore, ethical considerations were paramount throughout the study. All participants provided informed consent before participation, understanding their rights to confidentiality and the voluntary nature of their involvement. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board, safeguarding the well-being of the participants while ensuring the integrity of the research process.

This methodological framework not only strengthens the validity of the findings but also allows for a nuanced examination of how self-reported historical TBIs affect cognitive health in older adults, laying the groundwork for subsequent analysis of this critical public health issue.

Key Findings

The analysis of data from the Uniform Data Set (UDS) version 3.0 yielded insightful findings regarding the cognitive and functional outcomes for older adults with and without a self-reported history of traumatic brain injury (TBI). Initially, the statistical comparisons revealed that older adults with a disclosed history of TBI exhibited significantly lower scores across various cognitive domains measured by the UDS. This encompassed critical areas such as memory recall, executive functioning, and language ability, which are essential for daily functioning and maintaining independence.

More specifically, the results indicated an average reduction in cognitive scores reminiscent of a decline typically associated with a higher chronological age or neurodegenerative conditions. For instance, participants with a history of moderate to severe TBI showed an average decrease of approximately 1.5 standard deviations in their overall cognitive function scores compared to their counterparts without such injuries. This marked difference underscores the detrimental and residual effects of head trauma, even years after the initial injury.

Interestingly, the analysis did not merely show differences in cognitive performance but also highlighted variations in functional assessment scores. Those with a history of TBI were significantly more likely to report difficulties in activities of daily living, such as managing finances, preparing meals, and maintaining personal hygiene. This could suggest that cognitive impairments directly translate into practical challenges in everyday life, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions to support these individuals.

Further disaggregation of the data revealed that the severity and timing of the TBI incident were crucial factors influencing outcomes. For example, individuals who reported experiencing a TBI later in life exhibited more severe cognitive declines than those whose injuries occurred earlier. This time-sensitive relationship indicates that the cumulative effects of aging alongside earlier TBI might compound cognitive vulnerabilities, suggesting a developmental trajectory that warrants additional investigation.

In terms of demographic influences, the findings illustrated variations based on age and educational attainment. Older adults with lower educational levels presented with more pronounced cognitive impairments, irrespective of TBI history, suggesting that education may serve as a protective factor against cognitive decline. Meanwhile, social determinants such as living alone or a lack of social engagement were also seen in individuals with poorer UDS scores, indicating that psychosocial aspects might further exacerbate cognitive deterioration after a TBI.

Employing rigorous statistical models allowed the researchers to control for confounders, ensuring that the observed effects were indeed attributable to self-reported TBI history. This reliability in the findings enhances the validity of the conclusions drawn and suggests that healthcare practitioners should be particularly vigilant when evaluating older patients with a history of brain injuries.

The breadth of these findings emphasizes the substantive cognitive and functional challenges faced by older adults with a history of TBI. They compel a re-examination of assessment practices and highlight the necessity for personalized treatment approaches that take into account the nuanced impacts of head trauma history on aging individuals. As the aging population grows, understanding these dynamics becomes critical for informing clinical practices and public health strategies aimed at improving quality of life for this vulnerable demographic.

Implications for Future Research

The findings of this study highlight significant implications for future research focused on the cognitive health of older adults, particularly concerning the impact of traumatic brain injury (TBI). As the data suggests a pronounced effect of self-reported TBI history on cognitive and functional outcomes in older populations, future studies should further investigate the longitudinal progression of cognitive decline in individuals with varying histories of brain injuries. Longitudinal studies could provide insights into how cognitive abilities evolve over time and how the timing and severity of TBIs effectuate these changes. Understanding these trajectories could inform targeted intervention strategies aimed at preserving cognitive function in at-risk populations.

Moreover, exploring the biological mechanisms behind TBI’s effects on cognition in aging individuals is essential. Researchers could benefit from integrating neuroimaging studies that examine changes in brain structure and function post-TBI. Utilizing advanced imaging techniques such as MRI or PET scans to study neurodegeneration patterns could contribute significantly to distinguishing the specific neurobiological pathways affected by TBI and those related to typical aging or neurodegenerative processes. This intersection of neurobiology and epidemiology may uncover potential biomarkers for early detection of cognitive impairment following brain injuries.

Additionally, future research should consider the role of psychosocial factors in mediating the effects of TBI on cognitive health. The observations regarding social determinants of health, such as social engagement and living situations, point toward the necessity for multidisciplinary approaches that intertwine psychological and social support with therapeutic interventions. Investigating how community resources, social networks, and mental health services can mitigate cognitive decline in TBI-affected older adults can guide the creation of comprehensive support systems that improve their overall well-being.

A noteworthy avenue for future inquiry involves examining intervention efficacy. Given the identified cognitive impairments associated with TBI, it becomes crucial to evaluate existing therapies and assess new treatment modalities specifically designed for older adults with a TBI history. Cognitive rehabilitation programs, along with lifestyle modifications that promote mental and physical health, should be systematically evaluated for their effectiveness in enhancing cognitive performance and sustaining independence in daily activities. Multi-faceted intervention designs that incorporate physical exercise, cognitive training, and social engagement could prove especially beneficial.

Furthermore, as the research community continues to explore the implications of TBI across diverse demographic groups, attention should be given to variances in educational attainment, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity in relation to cognitive outcomes. This could enhance our understanding of which demographic factors modulate the impacts of TBI, thereby allowing for more personalized health management strategies. Addressing these disparities will warrant studies designed to assess the intersectionality of TBI with various social determinants of health, elucidating which populations may be at increased risk for adverse cognitive outcomes.

The findings from this study serve as a foundation for a range of future research endeavors. By addressing the complexities surrounding TBI effects on cognitive health in older adults from multiple angles—biological, psychological, and sociocultural—research can ultimately inform evidence-based practices that enhance the quality of life for this vulnerable demographic. As the aging population continues to grow, understanding the intricacies of TBI’s impact on cognitive health will become increasingly crucial for professionals involved in geriatric care and rehabilitation.